French🐱Chat

Today I’d like to teach you some words that you, as a speaker of English, probably already know! Many of these words and expressions have been used in English for so long, they no longer feel like borrowings to us.

The French language has had a huge influence on English since the time of the Norman Conquest of England (starting in 1066), when the invading forces from the north of France imposed their language on the English. English of course continued to be used, but members of the elite used Norman French, and over the ensuing centuries, many thousands of words of French origin made their way into the English language.

FOOD ITEMS

“[...] pork, I think, is good Norman-French; and so when the brute lives, and is in the charge of a Saxon slave, she goes by her Saxon name; but becomes a Norman, and is called pork, when she is carried to the Castle-hall to feast among the nobles.”

-- Sir Walter Scott, Ivanhoe

Nowadays, we commonly use the word “pig” to refer to the animal instead of “swine”, the ‘Saxon name’ used in this quotation. English words like “pork” and “veal” refer to the meat of the animals when it is to be consumed by humans, but the French words from which they derive are just the names for the animal, living or dead. For example:

pork -- from French porc, derived from the Latin porcus ‘big’. The English word “farrow” has the same origin, and the Irish cognate orc reminds us of J.R.R. Tolkien.

beef -- from the French word boeuf for ‘cow, ox’,which descended from Latin bovem (the accusative form of bos). This is one of my favorite examples of just how different descendants of a single word can become across diverging speech communities down through the millennia: Latin bos has the same source as English cow (and the archaic plural kine)! All these word-forms can be traced back to Indo-European *gʷōws (which is pronounced an initial labiovelar consonant).

mutton -- from the French word for ‘sheep’, mouton. This word came into French from Celtic, rather than being descended from Latin.

veal -- from the form veel in the Anglo-Norman dialect of French. The Modern French form of this word for ‘calf’ shows an interesting sound change: the word is veau, pronounced [vo]. Word-final /l/ weakened first to /w/ in Modern French, and the resulting /ew/ fused to a single vowel /o/. This change is also seen in the French word beau ‘beautiful’, which is the masculine form of the adjective. The feminine form is belle, where the /l/ did not weaken, as it was not word-final. Modern English has borrowed both male and female forms of this adjective as nouns: “the belle of the ball and her beau”.

COMPOUNDS AND PHRASES

déjà vu -- the name of that uncanny feeling that you have seen or experienced a certain situation before. This phrase is from French déjà, which means ‘already’ (related to Italian già and Spanish ya, all from Latin iam) and vu, a masculine participle meaning ‘seen’. The feminine form of this word, vue, is the source of the English word “view”. The infinitive is voir, which descends from Latin vidēre, and the word we use today is videō, which English has also borrowed. The words “vision” and “visit” have the same source.

raison d’être -- a phrase meaning ‘reason for being’. The French feminine noun raison is the source of English “reason” and is derived from Latin rationem (accusative of ratio, which English has also borrowed). The d plus apostrophe represents the preposition de whose basic meaning is ‘of’ or ‘from’, and which is therefore common in personal names derived from place names. This de is shortened to d’ when a vowel-initial word follows. Être is the infinitive ‘to be’ and is derived from Latin esse, with the redundant addition of the suffix -re (compare Italian essere). The Indo-European root of this verb is *es-, which also underlies English am, is, are, German ist, sein, Sanskrit asti, Greek esti, and so on. The French letter usually reflects the sequence -es- when the /s/ was lost before a consonant (compare fenêtre ‘window’, from Latin fenestra).

film noir -- the phrase means ‘black film/movie’, and really only the adjective is French, since as film was borrowed from English. This is therefore a case of re-borrowing! Note that here the adjective follows the noun it modifies. French adjectives may occur on either side of the noun, varying case by case, and sometimes the meaning of the adjective depends on its position with regard to the noun. French noir (masculine; the feminine is noire) comes from Latin niger, nigra, nigrum, and contains the only diphthong in Modern French, [wa], spelled -oi-.

joie de vivre -- a phrase meaning ‘joy of living/being alive’. The feminine noun joie (pronounced [ʒwa]) is the source of English “joy” and comes from Late Latin gaudia (gaudium in Classical Latin). The verb vivre ‘to live’ is from Latin vivere, which is related to the English word “quick” (which used to mean ‘living’) and the Greek stem bio- in words like “biography”, biology”, and “amphibious”. The Indo-European root of all these words also had an initial labiovelar consonant: *gʷīw- ‘to be alive’.

esprit de corps -- a phrase meaning ‘team spirit, morale’. Esprit is cognate with our word “spirit”, from Latin spiritus. “Sprite” is also derived from this Latin word. French speakers added the initial /e-/ to words with initial /s/ + consonant clusters (as in équipe ‘team’, from the Norse word for ‘ship’ with an initial sk-). In Spanish this happened as well in words like espíritu ‘spirit’ and estación ‘station’. The French word corps was borrowed into English on its own too (for example, in “Marine Corps”), and descends from the Latin corpus meaning ‘body’. Other derivatives of this Latin word include English corpse and Spanish cuerpo ‘body’.

Mardi Gras -- French for ‘Fat Tuesday’, a celebration period the day before Ash Wednesday, before the fasting season of Lent. The word Mardi reflects a compound of the divine name Mars (the Roman god of war) and Latin dies ‘day’. The English “day” is, perhaps surprisingly, not related to this Latin word. English “Tuesday” preserves the name of the Germanic war-god Tiw (Norse Týr). French gras (grasse in the feminine form) ‘fat’ is related to our word “grease” and descends (irregularly) from Latin crassus.

ENGLISH WORDS DERIVED FROM FRENCH COMPOUNDS

lieutenant -- a French Object-Verb agentive compound that means ‘one who holds a place’ and comes from lieu ‘place’ and tenant ‘holding’’. The noun lieu descends from Latin locus ‘place’ (itself also borrowed into Modern English, alongside many of its derivatives). The verbal element tenant is a present active participle, corresponding to English “holding”. The verb in French is tenir, which like its Spanish cousin tener ‘to have’, comes from Latin tenere ‘to have, to hold’. English derivatives of this root include “tenacious”, “retain”, “maintain”, and many others.

passport -- from passeport (the e is silent), another French compound, this time Verb-Object, meaning literally ‘to pass (through) a gate’. Both components have also been borrowed into English.

portmanteau -- from portemanteau, another French Verb-Object compound, meaning ‘carry-coat’, referring to a coat stand. Lewis Carroll in Through the Looking Glass extended this term to denote the type of word-blends he created for the poem “Jabberwocky”. His word “chortle” (a blend of “chuckle” and “snort”), one of the words coined in this manner, has since entered the English lexicon. A post-Carroll example of an English portmanteau word is “electrocute”, from “electric” and “execute”.

I hope this short tour through the French-derived English lexicon has been enjoyable! My hope is that making these connections between languages aids your memory when you’re learning vocabulary and piques your interest in language history. The table below provides a nice visual summary of what we have learned.

SYNOPSIS: LATIN TO FRENCH

This chart reviews all the French words we’ve looked at that are derived from Latin organized by the alphabetical order of the Latin words.

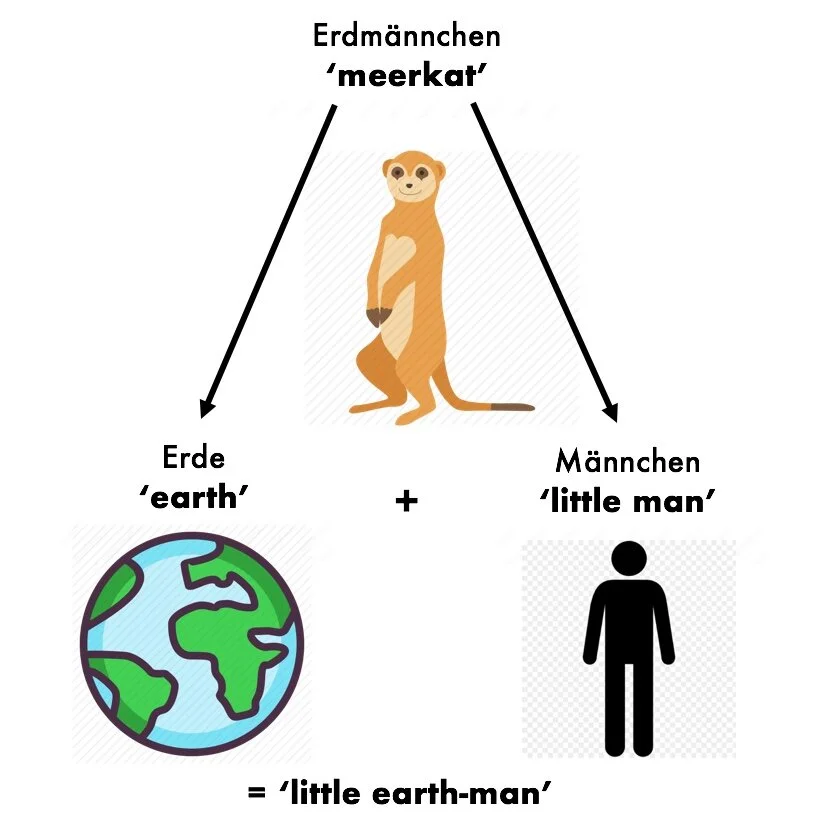

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!