Mighty Morpheme Word Arrangers: An Introduction to the Morpheme

In this post, we examine the notion of the morpheme, a fundamental unit of meaning in language. We look at a few different types of morphemes including stems and affixes. Learning about word building is useful for the language learner as it scaffolds understanding of how your target language works as whole.

Introduction

The morpheme is the most fundamental unit of meaning in language. That is, it is the smallest unit which has meaning. A word is made up of at least one morpheme and, in many cases, a word is composed of multiple morphemes. Morphology is the linguistic study of morphemes, or, in plain terms, the study of forms.

Table 1 illustrates some English morphemes. Looking at Table 1, we can start to get an idea what “smallest unit of meaning” looks like in language. The first example, “kind” is composed of a single morpheme. A morpheme that other morphemes attach to can be referred to as a stem. The next two examples each have two morphemes: something has been added to the stem “kind.” In the word “kindly” a suffix “-ly” has been added to derive an adverb (note, hyphens on a morpheme indicate which direction it attaches). In the word “unkind” an ‘un-’ has been added to the stem to derive a word with negative meaning.

Table 1: Some English morphemes.

Some types of morphemes

There are two primary types of morphemes: those that can stand alone, such as “kind” in Table 1, and those which cannot stand alone but must attach to something else, such as ‘-ly’ and ‘un-’ in Table 1. Morphemes which can stand on their own as words are called free morphemes, and those which must attach to something are called bound morphemes.

Words can be composed of a combination of free and bound morphemes. For example, in English we often combine free morphemes into compound words such as “racecar,” which combines the two free morphemes “race” and “car.” Another English example of a bound morpheme is the plural marker ‘-s.’

Recall that a morpheme that other morphemes attach to can be referred to as a stem. If we take “racecar” as our stem, we can attach the plural marker ‘-s’ to create “racecars.” Here, we can easily see that ‘racecars’ is composed of three morphemes: the two free morphemes “race” and “car,” and the bound morpheme ‘-s’ which adds the plural meaning. We challenge the reader to start counting morphemes in words, as it is not always as clear as “racecar”!

Linguists often distinguish types of bound morphemes including particles, clitics, and affixes. For the sake of brevity this blog only discusses the affix, but please contact us at LanGo if you are interested in advanced lessons on morphology (very useful for language learners and highly recommended for first-year graduate students of linguistics).

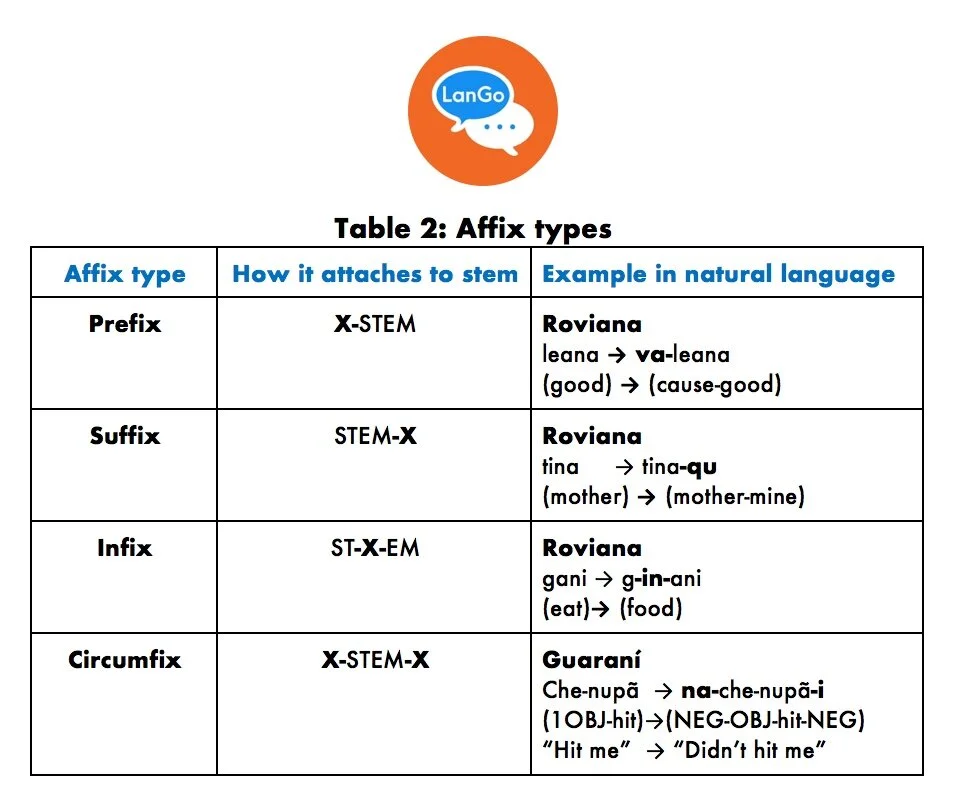

AFFIXATION: a quick ’fix

There are four salient types of affixes found in the world’s languages. The affix types, demonstrated in Table 2, are classified based on where they attach to the stem: prefix, suffix, infix, and circumfix. A prefix attaches to the beginning of a stem, a suffix attaches to the end of a stem, an infix attaches inside of a stem, and a circumfix attaches to both the front and back of a stem.The examples in Table 2 comes from Roviana, a language of Solomon Islands (South Pacific), and Guaraní, a language of Paraguay. Can you think of English example of each type of affix?

Table 2: Affix types.

We have already demonstrated prefixes and suffixes with our examples in Table 1, “un-kind” and “kind-ly.” Some argue that there is a profane infix in English which is applied productively! I dare not type the profane word, yet I predict almost all native speakers will guess the word once they see the pattern.

For example in the word “absolutely,” native speakers of English know that one profane word which rhymes with ‘ducking’ can be infixed to create “abso-ducking-lutely.” This infix (if that’s what it is) can only appear in certain places. Native speakers will not like forms such as “ab-ducking-solutely” and “absolute-ducking-ly”! Though this infix is not used in polite speech, let alone academic writing, native speakers certainly use it in casual speech and, sadly, it is the best example of an infix in English.

Does English have a circumfix? Well, some might argue that a word like “embolden” contains a circumfix. The word “bold” is clearly a free morpheme, as it can stand on its own and act as a stem. The word *embold, however, does not exist (that’s what the preceding asterisk marks) and has no meaning in English. Nor does the word *bolden exist. The only way to use the em- prefix here is in combination with the suffix -en. (For contrast, consider words like “em-body,” “em-power” versus “strengthen,” “widen.”) The argument that em-STEM-en is a circumfix in English is strengthened by the novel use of the made-up word “embiggen” (based on “big”) in the motto of the fictional town of Springfield from The Simpsons: “A noble spirit embiggens the smallest man.”

Morphophonemics in action

We can study morphological processes from two perspectives: how they change sounds, and how they change meaning. For the remainder of this post, we will focus on morphophonemic processes—that is, how sounds change when morphemes are added to stems.

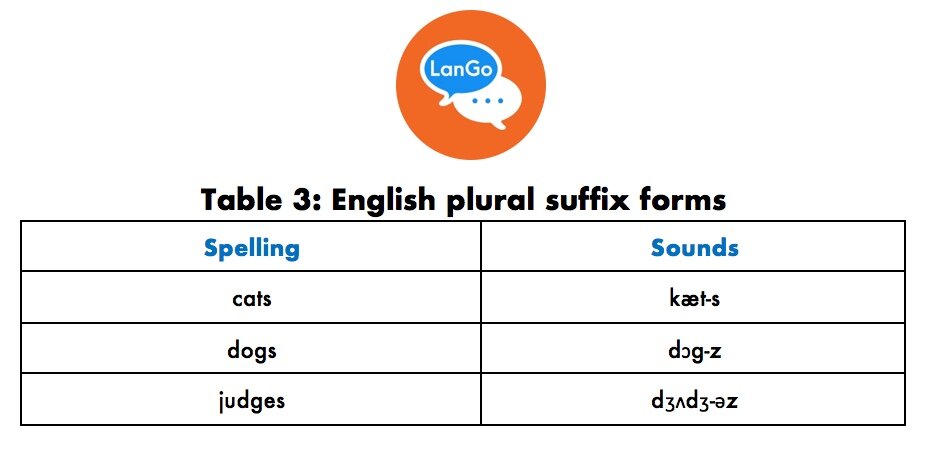

A great example of a morphophonemic process in English is the plural suffix, which is spelled with ‘s.’ Even though it is spelled with a single letter, the English plural suffix actually has three different phonetic forms! Table 3 illustrates the three different forms of the English plural suffix: [-s], [-z], and [-əz].

Table 3: English plural suffix forms.

These forms are not randomly assigned! We don’t say [kæt-əz] or [dɔg-s]. There is a consistent pattern as to which form the plural takes. As a hint, recall the description of “voicing” from the Lango Blog “Sound Features.” We observe that the [-s] form generally attaches to stems which end in a voiceless sound, and the [-z] attaches to final voiced sounds. But what conditions [-əz]? It might help us discover a generalization to examine more words which are pluralized with [-əz].

Table 4 illustrates words with different final sounds that all get the [-əz] plural. It is worth noting that the English spelling of these words adds a vowel that separates the last consonant sound from the plural!

Table 4: Stems that take plural [-əz].

Table 4 shows a pattern, namely that the [-əz] only occurs after the six sounds [s, z, ʃ, ʒ, tʃ, dʒ]. Linguists group these sounds into a class called “sibilants.” The English language prohibits the plural marker from attaching directly to sibilants, so a small vowel, [ə], is inserted.

Now that we know about the avoidance of sequential sibilants in English, we can revise our earlier generalization about when [s] and [z] attach! Let’s say that [s] attaches to non-sibilant voiceless sounds, and [z] attaches to non-sibilant voiced sounds. We only need to propose that a [ə] is inserted after sibilant sounds when attaching the plural, because we know that vowels are voiced and thus the basic plural marker [z] will follow the inserted vowel.

Conclusion

Knowing how to build words in a new language is a crucial skill for any language learner. The patterns of which sounds change when they touch other sounds, and which sort of sequences are permitted, varies from language to language. However, a language learner has an edge if they are aware that sounds will change when they touch other sounds because they can then generalize patterns. This sort of pattern generalization will reinforce existing knowledge and help the learner acquire new words and morphological processes.

![Table 4: Stems that take plural [-əz].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bb3b241e8ba44ae9c39e05b/1610730807374-UQK7X22XVNCGC79IUZDJ/Table4.jpeg)

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!