Sense and Syllabicity, Part 1: Syllable Sense for the Language Learner

Introduction

In LanGoPod episode #3 we discuss the important notion of the syllable and how this can be helpful to you as a language learner.

What even is a syllable? It is the basic rhythmic unit in human speech!

One easy way to think of the syllable is, as Tyler puts it, “a mouthful of speech.” That is, the syllable generally coincides with the time between when we open and close the mouth while speaking. Vowels are fundamentally open-mouth sounds, and consonants are closed-mouth sounds.

The syllable is the most fundamental unit for the language learner to describe and understand phenomena in many target languages; however, note that linguists also propose alternate types of rhythmic units, such as the mora. The interested reader should listen to LanGoPod episode #3 where we discuss, among many other things, the mora as a rhythmic unit in Japanese.

Anatomy of a Syllable

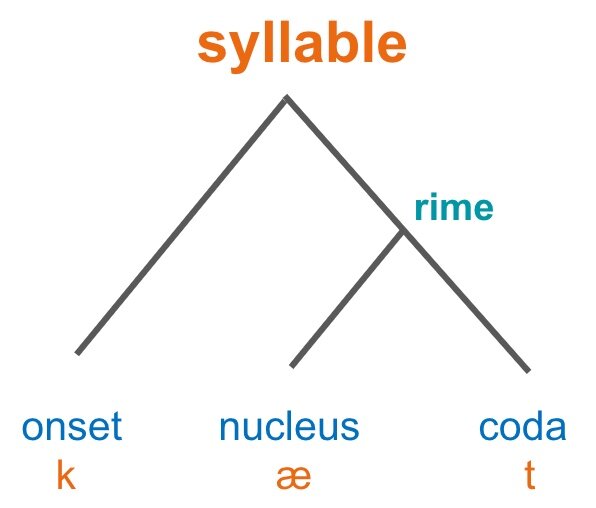

The syllable is built around a central sound, typically a vowel. We call this sound the nucleus. Consonants which precede the nucleus within the same syllable are called the onset. Consonants within the same syllable which follow the nucleus are called the coda.

Figure 1: Syllable structure of the word “cat.”

In Fig. 1, the single syllable making up the word “cat” is broken down into its parts. The first consonant sound in the word, /k/ (spelled with the letter “c”) is the onset. The vowel /æ/ is the nucleus, and the final sound /t/ forms the coda.

To make generalizations when we describe syllable shapes, it is useful to represent consonant sounds with a capital “C” and vowel sounds with capital “V.” In Fig. 2, the syllable “cat” is represented as CVC. It is sometimes helpful to think of the nucleus and the coda as having a special relationship. This grouping of nucleus and coda is called the rime.

Figure 2: The interior structure of the syllable.

A syllable can be described as either light or heavy, depending on what is in the rime. If the syllable has a nucleus but no coda, it is a light syllable. If a syllable has something in the coda, whether it is a consonant or a lengthening of the vowel, the syllable can be described as heavy. For a small selection of English examples of contrasting light and heavy syllables, consider the words in Table 1. Consonants are represented with C, vowels are indicated with V, and long vowels are indicated with VV. The dot (.) represents a syllable boundary

Table 1. Light and heavy syllables in English.

Landing Spot for Stress

The syllable as a rhythmic unit is best thought of as a general “landing spot for stress.” That’s because stress is manifested differently from language to language, and often isn’t even reducible to a single key feature in any given language. For example, in English the “acoustic correlates” of stress are duration (length), amplitude (volume), and pitch (intonation). That is, stressed syllables tend to be longer and louder than unstressed ones, and are typically the center of changes in pitch.

This basic notion of the syllable as a landing spot for stress is very useful for language learners. One insight from modern phonology that is particularly useful is the Weight to Stress Principle (abbreviated WSP). This principle proposes that stress is more likely to occur on a heavy syllable than on a light syllable. This is most noticeable in languages that have regular stress patterns that have variant patterns under certain conditions. A great example of how WSP works is stress shifts in Portuguese verbs in tenses other than the present.

WSP in Portuguese

Portuguese displays regular “penultimate” stress, that is, stress typically goes on the second-to-last syllable of a word. For example, in the two-syllable word cinco ‘five,’ the stress is on the first syllable. Recall that a period (.) is used in Table 2 below to indicate syllable boundaries in the phonemic forms.

Table 2: Regular stress patterns in Portuguese.

In typical three-syllable words, like cachorro (‘dog’), the stress falls on the second (and also penultimate) syllable. When the word cachorro is modified to form a diminutive (which adds the meaning ‘small’), as in cachorrinho ‘puppy,’ the stress consistently appears on the penultimate syllable.

This pattern is preserved in present-tense verb forms, as in Table 3:

Table 3: Portuguese present tense verbs with regular stress placement.

The pattern of penultimate stress has variation in past-tense and infinitive verbs, however. In Table 4 the infinitive form of ‘to know,’ a final consonant is added, /h/, which makes the final syllable heavy. In the past tense form ‘I swam,’ the final vowel is long, which also makes its syllable heavy. Thus, both words display final stress rather than the regular penultimate stress pattern we saw in the present-tense forms.

Table 4: Portuguese past tense and infinitive verbs with final stress placement.

In some instances, the present-tense 3rd singular form of a verb is very similar to the past-tense 1st singular form of the verb, except for the stress. Table 5 illustrates verbs whose tense inflections are primarily distinguished through stress.

Table 5: Stress in the Portuguese verbs ‘to drink’ and ‘to speak.’

The uninflected forms <beber> ‘to drink’ and <falar> ‘to speak’ have final stress, which follows from the WSP as they end in a consonant, which makes that syllable heavy. The inflected 1st person and 3rd person forms with different tenses use the same final vowel.In beber, the 3rd person singular present tense and the 1st person singular past tense both end with the vowel /i/. The past-tense form has a long vowel which attracts final stress, but the present-tense verb does not have a long final vowel, so it receives the regular penultimate stress. In the case of falar, the ambiguity is seen in the 1st-person present tense and 3rd-person past tense, which are primarily distinguished by vowel length and stress. The past tense, again, has the longer final vowel and the final syllable becomes the stressed syllable. One might propose that it is stress shifting to the final part of the verb which, in fact, causes the long vowel to appear. Regardless of the analysis, these examples of stress patterns clearly show the value of the notion of syllable structure and WSP to a Portuguese learner.

Linguistic notions and representations help learners make sense of their target languages and this is precisely why we created our podcast, LanGoPod! Having a framework to observe patterns and make generalizations is particularly useful for language learning situations where one will constantly encounter novel words, phrases, and utterances. Stay tuned for a forthcoming blog post with two more examples of “syllable sense” from Korean and German.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!