From "JOMO" to "Doomscrolling": New English Words for These “Quarantimes”

“Quarantine culture.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

Language is a living, dynamic system that is always changing across space, social groups, and generations. Language changes in order to adapt to the needs of its speakers, as new experiences require new ways to convey them clearly and efficiently (among other reasons). As a result, pronunciations evolve, morphology develops or decays, new words can be borrowed in or created, and the meanings of old words can even drift or expand!

One of the most salient ways that languages change is through new words that enter the lexicon. New words or expressions entering mainstream use are called neologisms (pronounced [niˈɑlədʒɪzəmz]), and the specialized language of particular social groups that arises outside of conventional usage is called slang. Younger speakers, in particular, are often influential early adopters of neologisms and slang.

Language change usually occurs so slowly that we hardly notice. This year, however, we have seen the rapid spread of new words which has been catalyzed by a profound and sudden social change: the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has radically changed our world, forcing us to adapt to new ways of organizing our personal lives, working from home, and maintaining social relationships. Even so, the Internet and social media have allowed us to stay connected while remaining physically distanced, and have even led to virtual experiences we might never have had before (for instance, here at LanGo, we’ve moved our conversation hours online and have found many novel ways to make our online language programs just as fun and interactive as our on-site ones).

In this post, we highlight some of the most salient neologisms and slang that have entered our lexicon in this relatively short span of time. The English of 2020 is worthy of its own dictionary, and we’ve organized some of our favorite new words into the following themes: words for the pandemic itself, existing words put to new uses, words for quarantine culture, and online jargon (because we’re online so much more now). These words demonstrate that, just as we ourselves have had to quickly adapt to a new reality because of the pandemic, so too has our language!

New terms for the virus. Illustration by Trinity Points.

Words for the pandemic

Coronaviruses (derived from Latin corona, meaning ‘crown’ [also the source of our word “crown”], and virus, originally ‘poison’) are a class of viruses named for the crown-like spikes on their surface. Many coronaviruses have infected humans since the mid-1960s. They are referred to as “new human coronaviruses” when they originate in animals and then evolve upon contact with humans. Examples of new human coronaviruses include SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome).

By March of this year, another new coronavirus had spread to most corners of the world. We first heard it called the novel coronavirus, differentiating it from other coronaviruses that commonly circulate among humans and cause mild illnesses, like the common cold. We then heard it called by its more scientific classification, COVID-19, a portmanteau of the words “corona,” “virus,” and “disease.” Now you may hear it called the Rona, or the Ronies (with the first syllable dropped, as it’s unstressed). Because of the fear and confusion surrounding the virus, other morbid portmanteau words like coronapocalypse and coronageddon have also been coined.

“Social distancing.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

Existing words put to new uses

As the virus began spreading around the globe, world leaders tried to think of the best ways to combat it. From medical professionals and government leaders, we began to hear phrases like “social distancing,” “flatten the curve,” and “six feet apart,” and before we knew it, these phrases had become a part of our everyday speech. All of these expressions existed before the COVID-19 outbreak, but in the new context of the pandemic, they became much more widely used and familiar to the general public.. “Social distancing,” somewhat of an oxymoron, involves encouraging people to stay at least six feet away from one another and to abstain from social gatherings. “Flatten the curve” initially referred to an iconic predictive graph that showed how overwhelmed hospitals would become if we didn’t keep COVID-19 rates low. Over time, the meaning of the phrase extended to include the notions of being responsible, staying away from others, and preventing the spread of the virus.

“Flatten the curve.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

This year, we have all had to adjust to a new normal. This term in itself feels a little self-contradictory and uncomfortable too; something that is “normal” shouldn’t be new—it should be our everyday life that we are used to. Yet this is a phrase we now hear and think about often. Before this year, the phrase “new normal” may have referred to major lifestyle changes like starting a new job, moving to a new city, or having a baby. But now this phrase evokes much bigger sociocultural changes, such as the rarity of social gatherings, canceled events, hand sanitizer bottles everywhere, the wearing of masks, working from home, and having to quarantine. This extension of the meaning of “new normal” aptly demonstrates that our culture has experienced a dramatic shift.

“New normal.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

Words for quarantine culture

The word quarantine also became salient this year, as the answer from trusted medical authorities to how we may best “flatten the curve” and reduce COVID-19 cases. This word has a fascinating history: it’s derived from French quarantaine meaning ‘(period of) about forty (days),’ ultimately from the Latin numeral quadraginta ‘forty.’ (This latter word is also the source of Italian quaranta and Spanish cuarenta, among others.) Today, this word refers to the designation by medical professionals of a 14-day period of separating and restricting the movement of individuals who may have been exposed to a disease.

“Essential worker.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

During a period of quarantine, people are encouraged or ordered (in many states) to stay home and shelter in place unless one is an essential worker (i.e., an individual who performs tasks critical for society to function, such as a medical professional or supermarket employee). WFH (“work from home”) became the “new normal.” Essential workers geared up with their PPE (an initialism for “personal protective equipment”), while the rest of the world worked from their couch, sporting athleisure (a portmanteau of “athletic” + “leisure wear”) and other WFH chic attire. Quarantine culture was born. People turned to new hobbies or rediscovered old ones to occupy their time at home. Families and roommates quarantining together spent more time together. Banana bread was made, TikTok became a major source of entertainment, and Joe Exotic (from the Netflix docuseries Tiger King, released early on during quarantine) became a household name. “Quarantine” then gave way to a multitude of new words: quar became the shortened term, quaranteam referred to the group you were quarantined with, and quarantini became the quasi-official name of any adult beverage you consumed during these quarantimes.

The “quarantini.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

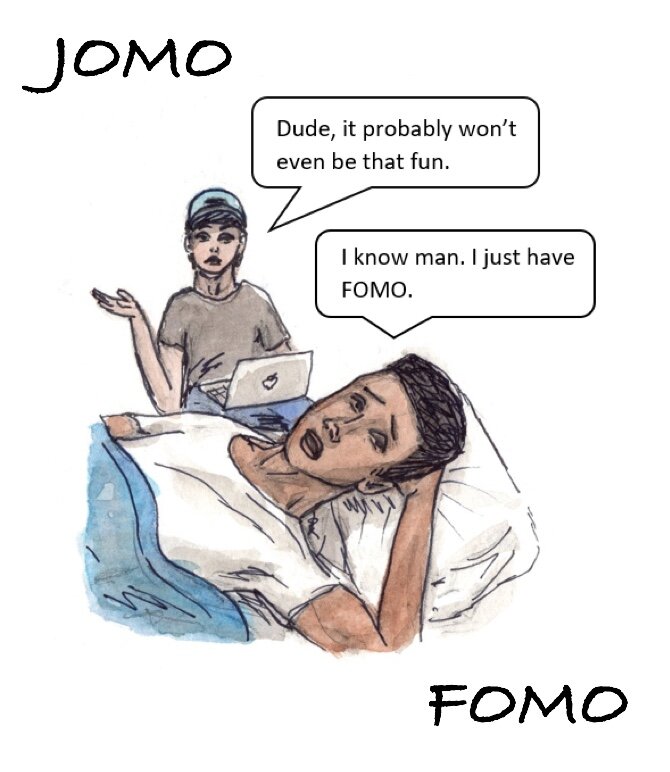

Before the pandemic, FOMO (an acronym for “fear of missing out”) referred to the desire to stay continually connected with what others were doing. This feeling was associated with compulsively checking for status updates and messages on social media, for fear of missing a social opportunity. As everyone adjusted to staying home in the first half of the year, for some, the meaning of FOMO extended to the feeling of mourning for our “old normal” lives characterized by parties, and vacations, and epic fun times. For others (who previously always thought they should be doing something more fun/adventurous/social/exciting/productive), it may have been blissful to hibernate at home for a while without a sense of guilt. In fact, for many, shifting into a JOMO mindset (short for “joy of missing out”) allowed them to appreciate the positive aspects of their new ways of life.

“JOMO” versus “FOMO.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

Online jargon

With more people online than ever before due to quarantine, new jargon (specialized terms used in particular fields, areas of activities, and communicative contexts) for doing things online has also entered our lexicon. Most WFH and “social” events have taken place on video conferencing apps, the most widely used one being Zoom (the app of the year, according to Apple). The word “Zoom” itself can now be used as a verb (distinct from its older sense of “to move quickly”) and there’s an entire lexicon related to using it. For instance, during a public Zoom meeting (i.e., one without a private link or password-protected setting), one might be unfortunate enough to experience a Zoombombing (the unwanted disruptive intrusion of an uninvited participant into a video-conference call). As another example, Generation Z-ers (those born roughly between 1995 - 2010) have easily adapted to doing even more things online and have earned the new nickname Zoomers. This word is a play on both “Zoom” and “Boomers,” the Baby Boomer generation being those born not long after World War II (approximately between 1946-1964).

“WFH.” Illustration by Trinity Points.

The virtual interface has become so interwoven in many of our daily lives that it’s no surprise that much online jargon has emerged, allowing us to work and communicate more effectively using it. We’ll turn next to terms related to hosting a virtual meeting. The all-powerful host of a meeting has the ability to share their screen, admit others into the meeting, and even kick out or mute unwanted participants. To make someone host or to give someone host means that the current host can give their “hosting powers” to another user. As a host, you can share things on your screen with all other individuals in the call, such as presentations, your Internet browser, or even a mirror image of what you see. The host, and other participants with access, can also take screenshots. Although this is not new online jargon, the use of “screenshot” as a verb (i.e., to take a picture of your computer or phone screen) is new. One grammatical point that’s especially interesting to us at LanGo is the debate as to how the verb “to screenshot” forms its past tense. According to an Instagram poll we recently ran (in response to @TermyCornall’s tweet; see below), most LanGorinos prefer “screenshot,” while a minority prefers “screenshotted.”

Perhaps one of the most salient new terms for online activity is doomscrolling -- the activity of scrolling endlessly on the Internet, reading post after post, article after article, and becoming anxious about all the uncertainty that “Rona” has brought with it. Aside from the pandemic, a number of “social plagues” also added to the uncertainty of the world this year. These included not only incidents of racism and bigotry, devastating natural disasters and eco-anxiety, and discord about politics and the presidential election, but also the subsequent “cancellation” of people, businesses, and even ideas deemed to be social nuisances. Cancel culture, a controversial and surprisingly recent coinage, refers to public pile-ons criticizing a person or business after they have done or said something considered objectionable or offensive. A much more optimistic coinage that refers to the activity of keeping up with the news online, and perhaps the antithesis of “doomscrolling,” is gleefreshing our feed (a portmanteau of “glee” and “refreshing”). This term started to pop up while people were avidly keeping up with the election results and news about a potential COVID-19 vaccine.

We hope this tour of new English words for these “quarantimes” has been both informative and fun, and that it has enriched your understanding of at least one aspect of this crazy year: the language we’ve used to describe it. Despite all that this year has challenged us with, thankfully the year ahead already looks brighter and more hopeful. Roll on, 2021. Because then we can really say “hindsight is 2020.”

What’s your favorite neologism or slang? Will 2020 “abso-2020-lutely” be the newest expletive? Will the once-popular phrase “going viral” (when a video or photo spreads rapidly across social media platforms) be “cancelled”? Share your thoughts with us on social @langoinstitute and join us tomorrow at the American Dialect Society virtual voting session for more words of the year nominations and selections.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!