To Infinitive and Beyond!

INTRODUCTION

This post accompanies LanGoPod episode #12, “To Infinitive and Beyond” in which we discuss the concept of the infinitive, and how it is best analyzed. We propose two competing analyses of infinitives as either nouns or verbs. Either analysis will help a learner categorize and acquire relevant aspects of the grammar of their target language. Relevant grammar points might include the grammatical expression of events which include multiple actions, events which take place outside of the present tense, and dependent clauses. Though infinitives might seem like a small grammar point, a good understanding of infinitives is critical for the proper acquisition of the target language.

The terms “finite” and “infinitive” refer to whether or not a word is marked for tense as in examples (a-c) with the verb “know”:

(a) She knows – the verb “know” is inflected to mark Simple Present.

(b) She knew – here it is marked Simple Past.

Verbs that have tense marking like this are called “finite.”

(c) It’s hard to know – here the same verb “know” is not so marked: we call this an infinitive.

In English, infinitives are often (but not always) preceded by the particle “to,” as illustrated in example (d).

(d) I like to eat pizza.

The labels “finite” and “infinitive” are reserved for verbs, as only verbs can bear tense and thus be “finite.” However, the word class of infinitive words, such as “to swim” or “to cook,” is not as clear. As we’ll discuss in this post, there are good reasons to analyze infinitives as nouns, and good reasons to regard them as verbs. In the end, we encourage language learners to use whichever analysis helps them learn and understand their target language.

Note on conventions:

* marks a phrase or sentence that is not well-formed.

[] is used for noun phrases: [a cake], [Liz], [we]

<> is used for verb phrases: <sleeps>, <bakes [a cake]>

a. [Liz] <bakes [a cake]>

b. *[Liz] <bakes [cake a]>

Infinitive as noun

Let’s first examine some evidence that supports the idea that infinitives are nouns. We can start with the observation that, in English, infinitives often occur in the same place a noun would occur.

Example (1) illustrates the complements of verbs such as “like” and “have.” A verbal complement is something that accompanies the verb, often as an object. On the left we see each verb with a simple noun phrase complement, and on the right, the same verb with an infinitive complement.

1) English: Infinitives occurring where nouns occur

a. I <like [chocolate]>. I <like [to <swim>]>.

(things I like are NOUNS: I like ___Noun)

b. I <have [time]>. I <have [to <go>]>.

(things I have are NOUNS: I have ___Noun)

We can form related sentences with these same words for (a):

c. Chocolate is what I like. To swim is what I like.

But if we do the same for the (b) sentences, the apparent parallelism begins to break down:

d. Time is what I have. *To go is what I have

The fact that infinitives occur in the same syntactic environments (meaning, roughly, the same slot in the sentence) as common nouns is a compelling reason to regard infinitives as nouns, or noun-like.

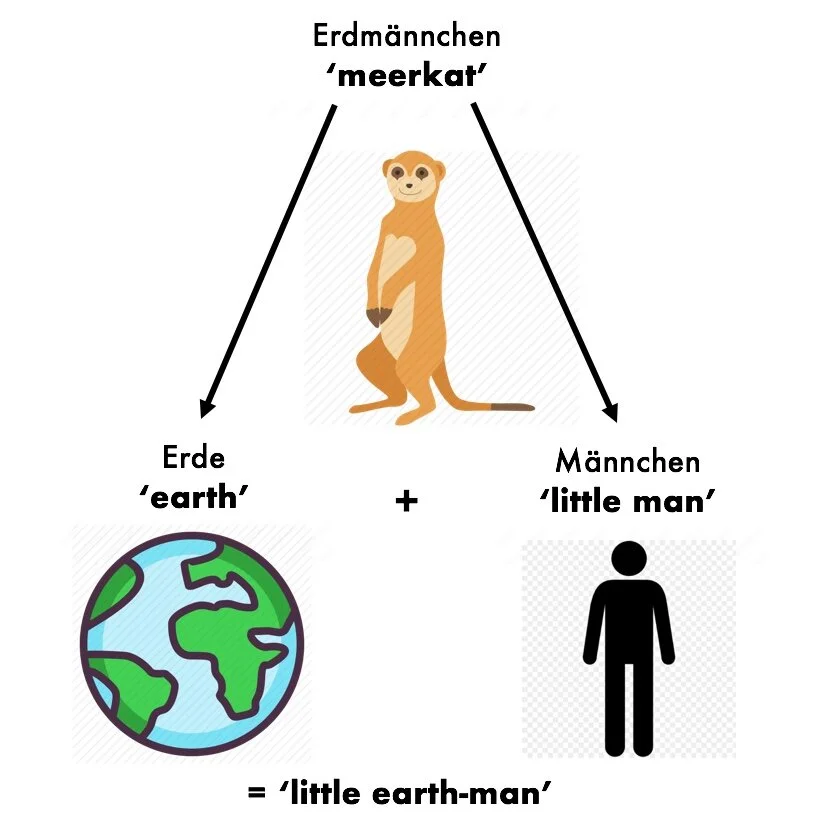

Looking beyond English, there are clear signs of the “nouniness” of infinitives in German, which has many related noun and verb pairs where the noun is homophonous with the infinitive. German nouns are capitalized, and are assigned to one of three genders, of which neuter (article das) is the default option for verbal nouns.

2) German

a. essen ‘to eat’ das Essen ‘food’

b. gefallen ‘to be pleasing’ der Gefallen ‘favor’ (masc.)

c. schreiben ‘to write’ das Schreiben ‘writing; letter’

Likewise in French and other Romance languages, many nouns are homophonous with infinitives, an important difference being that nouns have gender (shown by articles):

3) French

a. être ‘to be’ un être ‘a being’

b. savoir ‘to know (how)’

faire ‘to do’ savoir-faire ‘know-how’

An interesting case is plaisir ‘pleasure,’ which is an old infinitive of the verb whose modern form is plaire ‘to please, be pleasing.’

4) Spanish

a. poder ‘be able’ el poder ‘the power’

b. amanecer ‘to dawn’ el amanecer ‘the dawn’

Infinitive as verb

There are two important reasons why we might want to analyze infinitives as verbs. The first is that only verbs can bear transitivity. Evidence that infinitives can bear transitivity comes from the observation that they can take a direct object. The second reason is that even though infinitives cannot bear tense, they can bear aspectual contrasts. Only verbs can bear aspectual contrasts.

Transitivity in Infinitives

As you may recall from our blogpost on the topic, transitivity refers to the number of core arguments in a clause. A clause with one core argument is intransitive and a clause with two core arguments is transitive.

5) Intransitive and transitive examples in English

a. [Liz] sleeps.

Intransitive clause

b. [Liz] bakes [a cake].

Transitive clause

In English, it is easy to test if an argument is a subject because English has subject agreement for third person singular arguments in simple present tense. Also, we can substitute noun phrases for 3rd person singular pronouns and see if the argument is eligible for the nominative case with pronouns like “her” and “him.” However, it is not as easy to test if an argument is an object in English.

We need to know if an argument is an object to be certain that the clause is transitive and, thus, that the infinitive is a verb in a transitive clause. Example (6) illustrates the infinitive “to eat” with a variety of noun phrase complements. The noun phrase complements for “to eat” can be bare nouns, as in (a) or accompanied by modifiers as in (b-d). The observation that the complement phrases can contain numbers and articles supports the notion that they are noun phrase complements. However, (e) illustrates that the infinitive cannot be modified by determiners such as a definite article. This suggests that the infinitive itself is not a noun.

6) Determiners can accompany objects

a. I like to eat [pizza].

b. I like to eat [two pizzas].

c. I like to eat [the pizza] (that my grandmother makes).

d. I like to eat [a pizza] (on special occasions).

e. *I like the to eat pizza.

In order to thoroughly demonstrate that infinitive verbs can take objects, it might be more useful to look at a language which clearly indicates the status of an argument as being a direct object or not. For these reasons we look at the Roviana language spoken in Solomon Islands.

In the Roviana, all verbs must agree with the direct object if there is one in the clause. This means that the marker’s that appear with the verb form vary depending on what its object is. Examples (7a)and (7b) illustrate object agreement on bare infinitives in Roviana. In (a) there is third-person singular object agreement in a clause in which the subject of the dependent clause is the same as the subject in the main clause. In Roviana, when the subject of the main and dependent clauses are the same, the clause will have two verbs in a row, a phenomenon called “serial verbs.” In the serial verb construction in (a) the object agreement marker is attached to the bare infinitive, taka. In (7b), the subject of the dependent clause is different from that of the main clause. When the subjects differ in this way, the serial verb construction is no longer available and the infinitive verb is moved to the dependent clause and preceded by an infinitive particle, pude.

7) Roviana object agreement with infinitives

a. Same subject in dependent clause, use serial verb:

Hiva taka=ia rau sa siki.

want kick=[3SG.OBJ] [1SG] [ART dog]

‘I want to kick the dog.’

b. INF is clearer in switched-subject dependent clause:

Hiva=n=au Zone pude taka=igo.

want=APPL=[1SG.OBJ] [John] INF <kick=[2SG.OBJ]>

‘John wants me to kick you.’

In both examples, the infinitive verb is marked with object agreement, thus verifying its status as transitive. Nouns cannot take objects or be transitive, therefore the infinitives in Roviana must be analyzed as verbs.

Aspectual contrasts in Infinitives

One further piece of evidence that infinitives are verbs, suggested by Dr. William O’Grady (p.c.), is that infinitive constructions can bear aspectual distinctions, which is not something that nouns generally do. Recall that the distinction between finite and infinitive is one of tense, infinitives do not bare tense. Aspect is a part of grammar that is similar to tense, yet distinct.

Example (8) illustrates an infinitive construction which bears aspect. It is worth noting that the infinitive constructions can act as the subject of a clause! We would normally suspect that only nouns can be subjects, so how do we resolve this apparent conflict? The best answer is to propose that the entire infinitive phrase has been nominalized. Nominalization is a process in which elements which are typically not nouns are converted to nouns. Nominalization is a very common process and allows us to analyze infinitives as verbs while still accounting for the observation that they can sometimes act as the subject of a clause.

8) Infinitives can bear aspectual distinctions (h/t O’Grady)

a. [<To have finished on time>] is a huge accomplishment.

b. [<To be doing this work>] is rewarding.

c. [<To have been given this award>] means everything.

conclusion

In conclusion, there are two strong pieces of evidence to analyze infinitives as verbs:

1) Infinitives can take direct objects

“I like to eat [ (a/the/two) pizza(s) ]”

2) Infinitives can have aspectual contrasts (progressive, perfective)

“to finish,” “to be finishing,” “to have finished on time,” etc.

However, this is from a purely theoretical perspective. The language learner is encouraged to analyze infinitives as either nouns or verbs, depending on which analysis makes it easier to learn their target language. Keeping the noun-y aspects of infinitive in the forefront of your mind may, for example, help you in getting the right word order.

If you’re a person who enjoys listening to podcasts, we encourage you to check out our “To Infinitive & Beyond” episode. It presents more data and a few other arguments that are not included here.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!