Mandaringuistics, Part 2

INTRODUCTION

The Chinese writing system is thousands of years old, and over that time the forms of the characters (that is, the graphs used to represent the words of the language) have changed. The earliest written signs derived from simple symbols and depictions of real-world objects, and they consisted of a diverse array of shapes. As time went on the number of distinct strokes was reduced, and the writing materials changed as well. As a consequence of these developments, the look of the graphs evolved.

In more recent years, the look of Chinese has been updated once again, with the introduction of Simplified Characters b/简体字 jiǎntǐzì. These were created and propagated by the government of the People’s Republic of China starting in the 1950s, and they’re also used officially in Singapore.

In this post we’ll look at the various distinct ways that Traditional Characters (or 繁體字/繁体字 fántǐzì) were altered by the simplification. There are many dictionaries and online resources that can tell you which Traditional character corresponds to which Simplified character, but I’ve tried to do something a little bit novel here: I’ve grouped the simplifications according to eight major themes, or methods of simplifying. A few simplifications can’t be unambiguously assigned to any of these, so I list them separately at the end. I hope this will prepare you for all of the simplified forms you will encounter in your study of Chinese.

Method 1: Keep the basic shape but reduce the number of strokes

Consider the character 簡/简 jiǎn ‘simple, brief’ which we just saw in the paragraph above. It has three components, and is to be analyzed as follows (we’ll start with the traditional form):

簡 = 竹 + 間

竹 zhú ‘bamboo’ (in a slightly modified shape, which we call its “combining form” ⺮) is on top (as a meaning component), and 間 jiān ‘interval’ is on the bottom, chosen for its sound. This 間 is itself a compound character that includes:

間 = 門 + 日

門 mén ‘the gate’ is on top, and 日 rì ‘the sun; day’ is enclosed on the bottom.

The first of these components, 門, has eight strokes in its traditional form, and it is one of the graphs targeted for simplification by a reduction of strokes: its simplified form is 门, with just three strokes. This substitution of 门 for 門 is made in almost every graph with 門 as a component.

Now let’s put the components back together to get the simplified form 简 jiǎn ‘simple, brief’, the reverse of the analysis we just saw:

门 + 日 = 间 jiān

⺮ (竹) + 间 = 简 jiǎn

The 3-stroke graph 门 takes the place of the 8-stroke 門 virtually everywhere it occurs, as in:

們 -men (plural suffix) → simplified 们

閉 bì ‘to shut, close’ → simplified 闭

閃 shǎn ‘to flash’ → simplified 闪

The chart has more examples of this type of consistent substitution of abbreviated graphs.

An important subcategory of simplification method 1 involves substitution of a simpler graph only some of the time, rather than in every instance where the graph occurs. The 7-stroke “speech radical” 言 yán belongs here: when it occurs as the component of a character on the left side, it is always simplified to the 2-stroke form 讠(as in 语; traditional 語 yǔ ‘language’). But when it is written on the bottom, or occurs on its own, it retains its full traditional form. More such cases of most-of-the-time replacement are collected below.

Method 2: Replace phonetic component with a simpler one

The largest class of compound graphs in Chinese is called “Phono-Semantic Compounds”: graphs where one part is chosen for its sound and the other for its meaning. In simplification, phonetic components are often replaced with easier-to-write alternatives, as exemplified in the tables below. Sometimes the new phonetic component is chosen for its sound, as in (a), and sometimes it is chosen for its shape, as in (b).

Method 3: Omit meaning component, which creates new homographs

In a few cases of Phono-Semantic compounds, the Simplified form is created by dropping the Meaning component. The result is usually new homographic characters, which means that the simple graph takes on more meanings.

Method 4: Substitute homophone or similar-sounding character

Sometimes a complicated graph is simply dropped, and a similar-sounding character is used instead, again resulting in the simpler character taking on more meanings.

Method 5: Coin a new character

Occasionally completely new characters are created, discarding part or all of the traditional graph. The result may be a new Meaning+Meaning (or Signific) compound, as in (a) below, or a new Phono-Semantic compound as in (b).

Method 6: Replace meaning component

Rarely the meaning component is replaced by another that is simpler to write:

Method 7: Omit part of graph -- "Pars pro toto" (Part for the Whole)

In many cases half or more of a compound graph is simply discarded. This is comparable to alphabetic abbreviations such as English “cont.” for “continue(d)”, “est.” for “established”, “etc.” for “et cetera”, where the rule is: start writing the full word, and then stop once the combination of letters/graphs is distinctive enough to identify the word. Several examples are shown below.

Method 8: Arbitrary simplification

For a small number of high-frequency words, the relation of Traditional to Simplified form seems quite random. Some examples are shown below. One graph that is frequently chosen to take the place of more complex components is the 2-stroke 又 ‘and also’.

Special cases

For the two graphs representing words read as /fa/, a new simple form was chosen to unite two distinct characters in a single form:

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed this brief overview of Chinese characters. Whether you prefer to concentrate your study on the Traditional forms (in use for most of the last 2,000 years) or the modern Simplified characters (now used by 99% of literate Chinese speakers), you’ll want to at least be familiar with both systems. By tracing the various pathways from Traditional to Simplified forms, my aim here has been to make the challenging task of reading Chinese just a little bit more manageable for you.

再見 zàijiàn, until next time!

APPENDIX: Resources

Lexilogos - a useful tool for finding the simplified form of a traditional graph (and vice versa): https://www.lexilogos.com/keyboard/chinese_conversion.htm

Wiktionary - about as complete a dictionary of Chinese characters as I’ve seen, and includes traditional and simplified forms for every entry, as well as Japanese simplified forms: https://www.wiktionary.org/

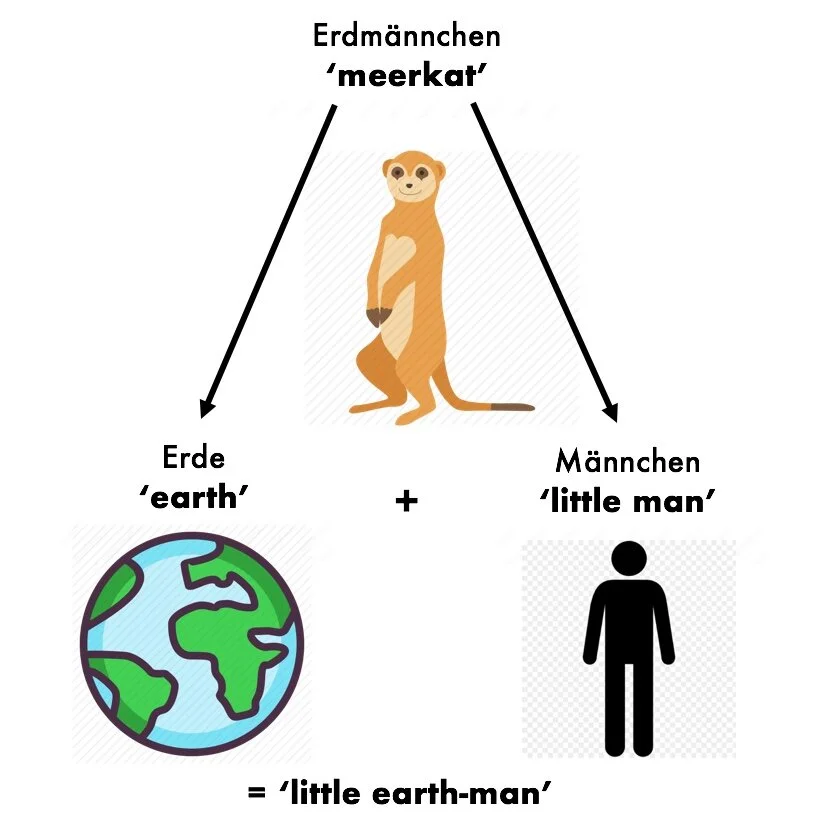

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!