Language Change: How Latin became Spanish

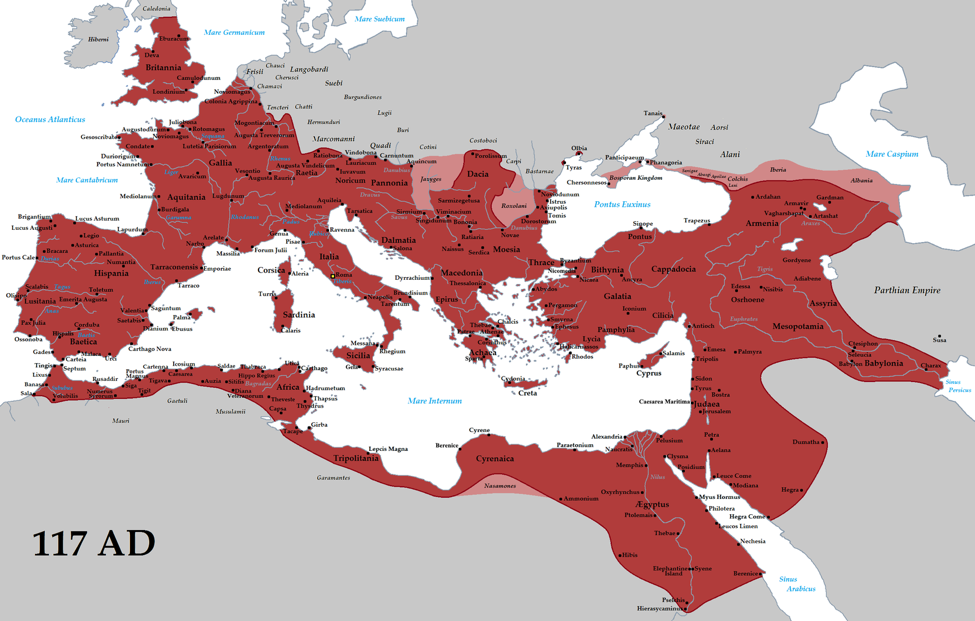

The extent of the Roman empire and areas (shown in red) with Latin speakers. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

[ Linguistic technical terms are defined in the Glossary. ]

INTRODUCTION

One of Marison’s Spanish students (who has knowledge of Latin and French) posed an excellent question in class the other day: “How and why do languages change?” This blog post is my attempt to answer this very intricate and fascinating matter.

To begin with, let’s consider what makes one language variety (whether a language or a dialect) different from another. For this overview I’ll draw on English, my native language. Then we’ll turn to Latin and Spanish below. We’ll proceed from the lowest level of linguistic structure, the speech sound, to higher and higher ones.

Different speech communities make use of different sounds. In my North American English speech I produce /r/ with a bunched-up tongue shape, while Scots speakers use a trill produced with the tongue tip.

Different speech communities use different words. This is likely the single most noticeable feature that delineates speech communities. What I call “soda” (carbonated soft drinks) English speakers elsewhere might call “pop” or “coke.” Many people in the U.S., especially in the south, use the pronoun “y’all” to specify plural addressees, while others use “yins/yinz,” “youse” or “you guys,” or uncontracted “you-all.”

Different speech communities may use the same words or phrases with differing meanings. The plural-only noun “pants” refers to different items of clothing in the UK and the US; “rooting for you” will convey something very different to an Australian from what it means to an American.

Different speech communities use different inflection patterns. In North America the participle of “get” is “gotten,” parallel to “forget : forgotten.” But in the UK people say “forgotten” with the en-suffix, versus “have got,” without it.

Different speech communities use different phrase structures. Whereas I would say “I’ve just eaten lunch,” a speaker of Irish English might instead use “I’m after eating lunch.” While my dialect uses these same words, the phrase as a whole has a different meaning for me: it sounds like the speaker is in pursuit of a meal, rather than just having finished one.

It’s important to note that just as these features differ from place to place within a language, so too do they differ from one time period to another. Even over my four decades (a short time in the life of a language) some perceptible changes have taken place within English:

“Cringe” used to be only a verb, but now it’s used as both an adjective (meaning ‘cringe-inducing, cringeworthy’: “That’s pretty cringe”) and as a noun (“You posted cringe”). Consider also the many new nouns (including names) that are used as verbs: “uber,” “email,” “google,” and the new senses of old words like “tweet” and “like.”

The verb “base” is now used with the preposition “off,” so that participial “based off” is in competition with the older “based on.” Perhaps these two expressions will coexist peacefully, or maybe one will outlive its competitor—I know of no way to accurately predict what will happen.

New prefixes and suffixes (and more!) have come into being: “e-” meaning ‘electronic’ has spread from “e-mail” to give new words like “e-commerce” and “e-signature,” while the ending of “litterati” has inspired the portmanteau words “glitterati” and “Twitterati.”

In some regions, English speakers are shortening certain long vowels and diphthongs before the consonant /l/, so “deal” comes to sound like “dill,” “real” like “rill,” and “nail” as if it were “nell.”

While this type variation goes back centuries within English, if not further, my impression is that more and more people prefer the past-tense verb form to the participle: “should have went,” “should have did” are threatening to oust today’s prescribed forms “have gone,” “have done.”

Each of these changes is unique when we regard it on its own, but bear in mind that these kinds of changes are nothing special: as far as we know such variation is always ongoing in every speech community, at every time and in every place. However much individual cases of variation may rankle us or set our teeth on edge, it’s helpful to adopt the perspective of a visiting Martian anthropologist: no linguistic variant is superior in any objective way; sounding good or bad is entirely in the eye or ear of the beholder, the result of long association of certain variants with prestigious or admired speakers.

Having surveyed some kinds of variation within English, we can now turn to the processes that, over 20 or so centuries “turned Latin into Spanish.” This kind of change is rarely abrupt: we’re not likely to find a date on which it would be meaningful to say, “Here’s when people stopped speaking Latin and started speaking Spanish.” Linguistic differences accumulate at glacial speed, and within a few generations, speakers in disparate corners of a defunct empire may no longer be able to understand one another. That is how the Romance languages came about after the Roman Empire collapsed.

DIFFERENCES OF SOUND

It is useful to divide speech sounds into vowels and consonants: vowels are fundamentally “mouth-open” sounds, and consonants are “mouth closed” sounds. Some consonants involve closure of the oral passage and have airflow through the nose: we call these nasals, and Spanish has the nasal consonants /m, n, ñ/. Some consonants also involve closure of the oral passage, with a quick build-up and release of pressure. We call these stops, and Spanish has the stops /p, t, k, b, d, g/. Other consonant sounds involve constriction of the oral passage but without closure. These sounds are called fricatives or continuants, and in this class Spanish has voiceless /f, s, x/, as well as voiced [β, ð, ɣ] as positional variants of /b, d, g/. There is one affricate /tʃ/ (spelled <ch>), which unites a stop with a continuant. Aside from these there are sonorant consonants /w, l, j, ʎ/, as well as long and short /r/. The upside-down y, /ʎ/, represents the palatal consonant in ella ‘she’ (English “brilliant” comes close).

As spoken Latin developed over the centuries in the Iberian peninsula, the following were some important changes. The diphthongs (double vowels) of Latin simplified: /ae/ became /e/, and /au/ became /o/. Then Spanish developed its own new diphthongs /ie, ue/ from low mid vowels (“L” stands for ‘Latin’):

L bene > bien ‘well’; L caecum > ciego ‘blind’

L bonum > bueno ‘good’; L somnum > sueño ‘sleep (noun)’

Velar consonants /k, g/ (made with the back of the tongue) shifted forward when vowels /i, e/ followed (square brackets enclose IPA symbols):

L centum [ken.tum] > cien(to) ‘100,’ with initial [s] or [θ]

L gentem > gente ‘people,’ with a palatal or “soft G,” which later became a velar fricative [x]

The Latin labiovelars /kʷ, gʷ/ lost the [ʷ] component when /i, e/ followed:

L quis, quem [kʷem] > quien [kjen] ‘who?’

L quaerere > querer [ke.rer] ‘want’

Initial clusters of /s/ plus a stop (or fricative) developed an initial vowel /e/:

L studium > estudio ‘study’

L scholam > escuela ‘school’

This development was carried further in French, where the /s/ was deleted, compare école [e.kɔl] ‘school’ from scholam, and the verb étudier [e.ty.dje] ‘study,’ based on the noun studium.

Word-initial consonants are otherwise mostly unchanged, but between vowels within a word, some restructuring took place: Latin double voiceless stops, held twice as long as the single, gave single voiceless stops in Spanish, while Latin single voiceless stops became voiced. This is well illustrated in these words:

L peccatum > pecado ‘sin’

L apothecam (from Greek) > bodega, ‘store, warehouse’ with loss of the initial vowel after /p/ had voiced to [b]

The sounds d and g in these words, though written with stop consonant letters, are actually pronounced in Spanish as voiced fricatives [ð, ɣ], as noted above, whenever they stand between vowels. Single Latin voiced stops tended to weaken or be deleted in the development of Spanish, but generally not /b/: this has not been lost but is pronounced as a voiced fricative.

L habere > haber [a.βeɾ] ‘have’; L bibere > beber [be.βeɾ] ‘to drink’

L vadimus > vamos ‘we go’; L includere > incluir ‘enclose, include’

L ego > yo ‘I’; L frigidum > frío ‘cold, frigid’

For an overview of sound changes see Table (4) below.

DIFFERENCES IN WORD MEANING

Aside from changes at the level of sounds, changes in the meanings of single words are important in the development of Spanish as we know it today. For example, the Latin verb miror, mirari meant ‘wonder, marvel at,’ a sense preserved in the English derivatives “ad-mire,” “miracle,” and “miraculous.” In Spanish, the reflex (“descendant word-form”) mirar has acquired a much broader range of meanings: ‘watch, look at, seek, look for,’ and so on.

Words acquiring broader or narrower senses is commonplace, but some changes in meaning are more surprising. The Spanish negative pronoun nada ‘nothing’ looks like it belongs historically to the family of negative words beginning with /n/ (based on Latin ne), including no, ní, nunca, ninguno, and so on. But the origin of the word is in fact quite different: it comes from the feminine participle natam ‘born’ (as in Eng. “neonate,” “natal,” from the Latin verb (g)nascor, nasci ‘be born’). How did the word ‘born’ come to mean ‘nothing’? It seems to have developed out of a phrase nullam rem natam, meaning ‘no born thing’; compare how Latin passus ‘step’ developed into the French negative marker pas, from phrases like “I won’t go a step.” In this and the Spanish phrase, the negative sense has been transferred (from nullam or ne) to a distinct word.

To conclude this section, let’s take a look at a very important set of Spanish words, namely the pronouns él ‘he,’ ella ‘she’ and the articles el/la ‘the,’ and how these forms developed. These developed from what in Latin were a single set of ‘pointing words’ (deictics) meaning ‘that one (over there).’ The meaning changed, on the one hand, to a simple pronoun ‘he/she/it,’ and on the other to the definite article ‘the,’ which Latin had no word for. Latin was a highly inflected language, so the form of words in noun phrases was adjusted to mark grammatical gender (masculine, feminine, neuter), number (singular/plural) and case (nominative mainly for subjects, accusative for direct objects). Here’s a partial paradigm of forms of the word ille (meaning ‘that (one)’) which are relevant to Spanish:

Table 1: Selected forms of Latin ille ‘that one’.

Out of these words arose two distinct sets of forms in Spanish. When Latin ille, illa etc. were used as pronouns (meaning they stood on their own, not in conjunction with a noun), the nominative forms seem to have been stressed or accented. The outcomes include both 1- and 2-syllable forms: 2-syllable pronouns for most subject pronouns (except singular el ‘he’ and lo ‘it’), while object pronouns are entirely single syllables. Selected Spanish pronouns reflecting ille, illa are shown in Table (2).

Note that the nominative plural forms illi, illae, illa are not preserved in Spanish; as with the nouns it is generally the accusative form that became the basis for Spanish word-forms.

Table 2. Spanish outcomes, part 1: Pronouns.

When Latin ille, illa occurred as determiners with a noun, the outcome was quite different. Here the stress would have tended to be on the noun itself, or maybe on an adjective or other word in the noun phrase. As a result, it’s entirely 1-syllable words in this set of reflexes of ille (Table 3).

Table 3: Spanish outcomes, part 2: Definite articles (meaning ‘the’).

Generally, where the Latin word had a second syllable ending in a consonant, it is that second syllable that survives in the Spanish form of the article; if that syllable ended in a vowel, then Spanish preserves the first syllable (ille > el).

The Spanish feminine article is pronounced la, with one notable exception: if the vowel sound immediately following is accented á (with or without silent h preceding), as in águila ‘eagle’ or agua ‘water,’ it is the first syllable of the old word illa(m) that is preserved. The outcome ellooks like the masculine article, but is in fact not: agua and águila remain feminine nouns (el agua fría ‘the cold water,’ not frío).

DIFFERENCES IN GRAMMAR & LEXICON

In this final section we’ll survey some developments in Spanish above the levels of sounds and the meanings of single words, followed by selected words that came into Spanish from languages other than the ancestral Latin. (“Lexicon” is a term for the stock of words in a language, the totality of speakers’ mental dictionaries.)

The 3-gender system of Latin, with its categorization of all nouns as either masculine, feminine, or neuter, is in fact preserved intact in Spanish, but the cases where a neuter word-form is distinct from masculine are very rare. An example is phrases like lo que me gusta ‘that which pleases me/that which I like,’ where lo is a subject pronoun (this is not the object lo!) that is not masculine (él) or feminine (la). The Spanish neuter gender is, as far as I know, distinguished from the masculine only in pronouns.

Latin was, as we mentioned, a highly inflected language, with five distinct noun cases plus a vocative used for addressing people (Sir! Ma’am!). Spanish still has distinct dative pronouns (le, les), but the functions of dative and ablative nouns are now relegated to prepositional phrases.

One instance where Spanish seems to have innovated a new case category involves the preposition con meaning ‘with.’ Where English uses the same words “me” and “you” following “with,” in Spanish we must use the special forms migo and tigo when the pronouns are used with con: “con mi” is incorrect, and we must instead say conmigo. (See here for a brief account of the origin of these words.)

Speaking of innovations in pronouns, Spanish speakers a few centuries ago elaborated the inherited Latin pronouns nos ‘we’ and vos ‘you plural’ with the reflex of alteri, alteros ‘others’: nosotros and vosotros now serve as the subject forms. Another important innovation is Usted ‘formal you,’ which arose as a contraction of vuestra merced ‘Your Grace.’ This is the reason Usted has 3rd-person verb agreement, though it refers to 2nd-person YOU.

In Latin the high degree of inflection on verbs allowed for multiple verb tenses expressed with single word-forms: from facere ‘to do’ we have facio (simple present), faciebam (imperfect), faciam (future), feci (perfect), feceram (pluperfect), and fecero (future perfect), as well as various passives and subjunctive inflections. As in other Romance languages, some new compound verb tenses arose in which an auxiliary is used with a participle or infinitive, as we have in English as well: the Modern Spanish perfect tense he hecho ‘I have done,’ has hecho ‘you have done,’ etc., corresponds piece by piece with our “have done”: inflected auxiliary HAVE plus past participle DONE.

As we have seen, Modern Spanish is a development from Latin as it was brought to Spain by the Romans two millennia ago. The core of the Spanish stock of words is a continuation of the inherited Latin vocabulary, showing developments in form and in meaning. But there are many other important sources of Spanish words:

Basque, the language isolate indigenous to the Iberian peninsula, is the source of many words such as vega ‘river plain,’ zorra ‘fox,’ izquierdo ‘left (hand),’ and mochil ‘errand boy,’ as well as names, Íñigo, Javier, and Vasco among them. Many “Spanish” surnames are in fact of Basque origin, for example Echevarria (meaning ‘new house’), Bolívar (from the words for ‘mill’ and ‘river’), Izaguirre (‘clearing exposed to the wind’), and Elizondo (‘[house] beside the church’).

Several dozen Spanish words reflect another group of inhabitants of the Iberian peninsula, namely the Celts. Such words include álamo ‘white poplar,’ bruja ‘witch,’ correa ‘belt,’ garza ‘heron,’ and güero ‘vain, vacuous.’

Arabic is famously the source of hundreds of Spanish words. Many are readily identifiable by the Arabic definite article al- that is incorporated into the noun stem in Spanish: almuerzo ‘lunch,’ alfombra ‘carpet,’ algodón ‘cotton’ (originally meaning ‘Coptic, Egyptian’) and of course alcohol, which made its way into many European languages. Other words of Arabic origin are ojalá ‘I hope/wish,’ rincón ‘corner,’ and tarea ‘task.’

CONCLUSION

We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s survey of some aspects of the history of Spanish, even if you’re not currently studying Spanish. The ways in which languages change over the millennia is a topic of endless fascination to me personally, and perhaps this has made you curious about the development of your native language, or of other languages you study or have contact with.

One fun thing to consider, after you’ve learned some of the ways that sounds, words, meanings, and whole grammars change over time, is what changes the future holds for the languages we know and love today!

To conclude our survey, here are some Spanish words and their Latin ancestors showing the effects of some common sound changes.

LanGo is now on Twitch! Join us as we learn Spanish, Latin, Catalan and Guaraní (along with 30 other languages) on Duolingo.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!