Sound Features

If you tuned in for LanGoPod episode #1, you may recall that sounds are different from letters. Though we must never lose sight of the fact that words and utterances are made of sounds, not letters, it is still helpful to use alphabetic symbols to represent sounds. One important example of a set of symbols used to represent sounds is the International Phonetic Alphabet (for short: IPA). The IPA is a particular convention for representing sounds with symbols, and is used by linguists working all over the planet (unlike older writing systems).

In the IPA, each symbol represents a bundle of features (e.g. voiced/voiceless) that can be used to describe and define the sound. Vowels are described in terms of tongue position, jaw height, and the shape of the lips. Consonants are described using the place they are articulated in the mouth, the manner in which they are articulated, and the configuration of the vocal folds.

A note on the conventions used in this post: standard spellings are represented in <>, phonemic forms in //, and phonetic forms in [].

Sounds as Features

Linguists use features to describe a sound, and then use a phonetic symbol to represent the features. Vowels and consonants are both described with features.

VOWELS

Vowels are produced with virtually no constriction in the vocal tract. The sound of the vowel reflects the way the tongue, jaw, and lips affect the oral resonance chamber. Thus, vowels are typically defined by their frontness/backness, highness/lowness, and the roundness of the lips. The IPA vowel chart in Figure 1 illustrates the positions of a large set of oral vowels of the world’s languages. “Close” and “open”, in this chart, refer to what we are calling jaw height. Thus a “close” sound on this chart is a “high” vowel, and an “open” sound is a “low” vowel.

The position of the tongue—toward the front or back of the mouth—is described by means of two features: frontness and backness. Both features are described in binary terms, either plus (“on”) or minus (“off”). That is, a “front vowel” is both [+front] and [-back], and a “back vowel” is both [-front] and [+back]. A vowel produced with the tongue neither in the front or the back of the mouth, sometimes called a “central vowel,” is both [-front] and [-back]. No vowel can be both [+front] and [+back]!

Similarly, the position of the jaw during vowel production is described with two features: high and low. A “high vowel” (called “close” on the chart) is [+high, -low]. A low vowel (called “open” on the chart) is [-high, +low]. A vowel produced with a jaw height that is neither high nor low is called a “mid vowel.” A vowel cannot be both high and low at the same time!

Some vowels are produced with rounded lips, others with unrounded lips. This feature is referred to simply as “rounding.” Across languages, there is a trend that [+back] vowels are also rounded, and [+front] vowels unrounded. Some languages may have rounded front vowels or unrounded back vowels, but these unexpected pairings are considered “marked,” meaning they are unusual, less common than the other way around. There is an implicational hierarchy that languages with rounded front vowels will also have unrounded front vowels, and languages with unrounded back vowels will also have rounded back vowels.

These features can help you learn vowels in a new language, such as French, English, or Portuguese! For example, French contains a series of rounded front vowels. If a learner knows that the only difference between [i] and [y] is rounding, then they can practice starting with the [i] and then rounding the lips to produce [y]. Then the learner can extend this principle to similar vowel pairs at other vowel heights. In LanGoPod episode #2, Tyler gives a useful French mini-lesson using this very approach.

CONSONANTS

Consonants are described in terms of

their place of articulation,

the manner in which they are articulated, and

the configuration of the glottis and vocal folds.

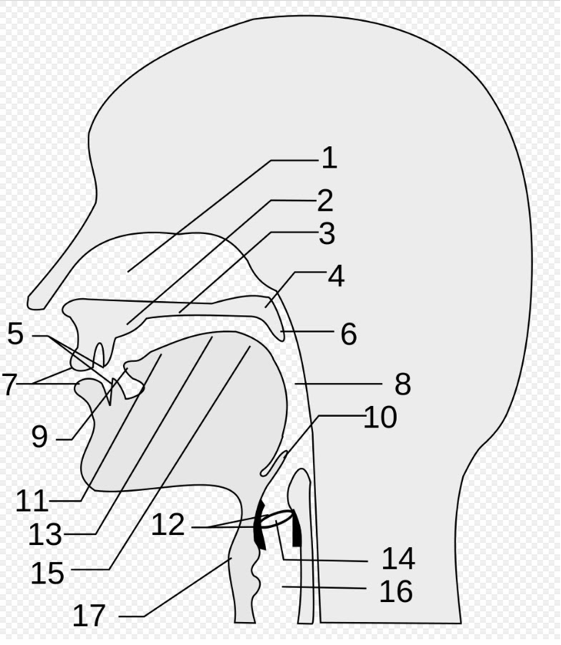

Looking at a midsagittal section of the human vocal tract is helpful for understanding consonant articulation. In the IPA consonant chart in Figure 2, the columns represent places of articulation (left to right), and the rows distinguish manners of articulation (top to bottom). Where there are two sounds in the same cell, the one on the left is voiceless and the one on the right is voiced.

As the organization of the IPA chart shows, consonants are grouped in terms of their place of articulation (top row of the table), manner of articulation (left column of the table) , and configuration of the glottis and vocal folds. Looking at a midsagittal section of the human vocal tract (see Fig. 3.) is helpful for understanding consonant articulation (the key is provided below).

There are two types of articulators: passive and active. An active articulator is one that moves, such as the tongue. A passive articulator, such as the top teeth, does not move. The active articulators include the bottom lip, the tip and back of the tongue, the uvula, and, in some cases, the glottis itself. The passive articulators include: upper lip, upper teeth, the alveolar ridge (directly behind the top teeth), the palate, the velum, and the pharynx. When describing the place of articulation of a consonant, linguists often merely refer to the passive articulator.

The manners of articulation can be organized into how “sonorous” they are (a sonority hierarchy as in Fig. 4), that is, how much more they constrict the vocal tract than vowels.

Fig. 4. Sonority hierarchy.

The consonants with the least constricted manner of articulation are called “glides” or “semi-vowels” and they include sounds like [j] and [w], they are almost vowels. (The [j] is the sound in “hallelujah,” not the one in “judge.”)

The next class is called “liquids,” and these consonants constrict the vocal tract even more than glides, but still allow lots of air to pass through. The two primary types of liquids are: rhotic liquids, such as /ɹ/, in which the tongue shape heavily colors the sound, and lateral liquids, which allow the air to pass laterally—over one or both sides of the tongue, exemplified by /l/.

The next class of sounds is “nasal stops,” for short just “nasals.” Nasal consonants typically involve a complete closure of the oral cavity while the velum lowers to allow air to pass through the nasal cavity.

Glides, liquids, and nasals together constitute the class of “sonorant” consonants, which involve relatively low degrees of vocal tract constriction. There is another class of consonant sounds called “obstruents” which involve much more constriction in the vocal tract.

The first class of obstruent sounds we’ll discuss here is fricatives. Fricative sounds allow the air to pass through the oral cavity, but, at one point at least, there is a very tight constriction where turbulent airflow creates a distinctive noise. Examples of fricatives include /s/, /z/, /f/, and /v/.

The next class is affricates. Affricates can be thought of as two sounds put together, and are even represented as such in IPA. Affricates begin as a complete stop (see below) in the oral tract and finish as a fricative. A typical example of an affricate is the sound /tʃ/ found at the beginning of the English word <cheese> [tʃiz].

The final class, stop consonants, involves the highest level of constriction: complete obstruction of the vocal tract. This class is exemplified by sounds like /p/, /t/, and /k/.

The final consonant feature that linguists usually include in descriptions is voicing. Voicing occurs when the vocal folds are held close but not entirely shut. See Figure 6 for different types of glottal configurations. When air passes over the vocal folds in this configuration, it causes the vocal folds to flap open and shut at frequent intervals. When the vocal folds are held open, a sound is said to be voiceless. Vowels are typically voiced, but not all consonants are. (Some languages, e.g. Mandarin and Japanese, feature voiceless vowels as well.) Sonorous consonants, such as liquids and nasals, are typically voiced. But, cross-linguistically, if a language only has a single set of obstruents they will be voiceless. It is common to find obstruents that only differ by voicing, such as the opposition between /z/ and /s/.

Fig. 5. Glottal configurations: A. Closed B. Voiced C. Whisper D. Breathing position E. Respiratory or resting position F. Deep breathing. Source: WikiMedia Commons (link).

Describing English Sounds in Features

The IPA chart for English consonant sounds is shown in Figure 6. Using the IPA to learn the English sounds is very beneficial because it can help you understand how to pronounce them.

Fig. 6. IPA chart of English consonants, with voiced consonant sounds shaded in gray.

Let’s consider two sounds that are difficult to pronounce for many learners of English: /θ/ versus /ð/.

English spells two different phonemes with the same orthographic convention, <th>. The two distinct sounds can both be described as interdental fricatives. The difference between the two sounds is that one is voiced and the other is voiceless. The voiceless one is represented in the phonetic alphabet as /θ/ (e.g. in <thin>), and the voiced one as /ð/ (as in <then>).

In order to test voicing you can touch your throat and hold each sound (see Fig. 7. for example English words with voiced /θ/ and voiceless /ð/). The one that has vibration, /ð/, is voiced, as in “breathe, thy, either, this,” and “the.” The one that does not have vibration, /θ/, is voiceless, as in “breath, thigh, ether, think,” and “thorn.”

Fig. 7. Examples of English words spelled with <th>, but pronounced with voiced /θ/ OR voiceless /ð/.

Using features to learn Portuguese spelling

In Portuguese, there are two letters which may be pronounced as [s]: <ç> and <s>. To further complicate things, the letter <s> may be pronounced as either [s] or [z]. Understanding features helps us to understand which pronunciation of <s> we should use.

<s> as [s] or [z]

In the Portuguese word suco, ‘juice,’ the <s> is pronounced as an [s]. But in the Portuguese word casa, the <s> is pronounced as [z].

SPELLING PRONUNCIATION MEANING

casa [kazə] ‘house’

suco [suku]* ‘juice’

In order to understand the difference, it is helpful to look at the features of [s] and [z].

[s]: +alveolar, +continuant, -voice

[z]: +alveolar, +continuant, +voice

[s] and [z] are very similar sounds, they differ by only one feature: voicing. This helps us predict when <s> will be pronounced as [z]! When a single <s> is between vowels, which are voiced themselves, <s> is voiced as well.

<s> versus <ç>

Despite how the graph <s> is pronounced in words like casa [kazə], voiceless alveolar fricatives can occur between vowels in Portuguese. The minimal pair casar ‘to marry’ and caçar ‘to hunt’ demonstrates this distinction.

SPELLING PRONUNCIATION MEANING

casar [kazah] ‘to marry’

caçar [kasah] ‘to hunt’

Conclusion

Thinking of sounds as a bundle of features can be very useful in learning a language which has sounds different from your native language. Quite often, the language you are learning will either distinguish sounds that your native language doesn’t, or it will fail to distinguish sounds that your native language does. Using knowledge of features, a learner can understand the differences in sounds and make meaningful predictions while learning. Sound features are useful in both pronunciation and listening.

This post offers only a small window into the usefulness of thinking of sounds in terms of bundled features! If you are interested in gaining a comprehensive understanding of sound features for language learning, attend (on-site or online) a LanGo linguistic workshop and enroll in a language program.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!