Tyler's Story

In this post I share about my life history and talk about my encounters with various languages. My early experience with European languages (Dutch and German) paved the way for an abiding fascination with how language works, and with using the diversity of modern forms of speech to reconstruct the past.

HOW I GOT INTO LINGUISTICS

The word “linguist” has two senses: the more recent sense refers to a scholar of natural languages, the way a physicist is a student of natural phenomena. The older sense was ‘language enthusiast’ or ‘one who is well versed in languages’.

Before I became a linguist in the younger sense, I was a linguist in the older sense. I cannot recall a time when I was not fascinated by languages.

Family Background

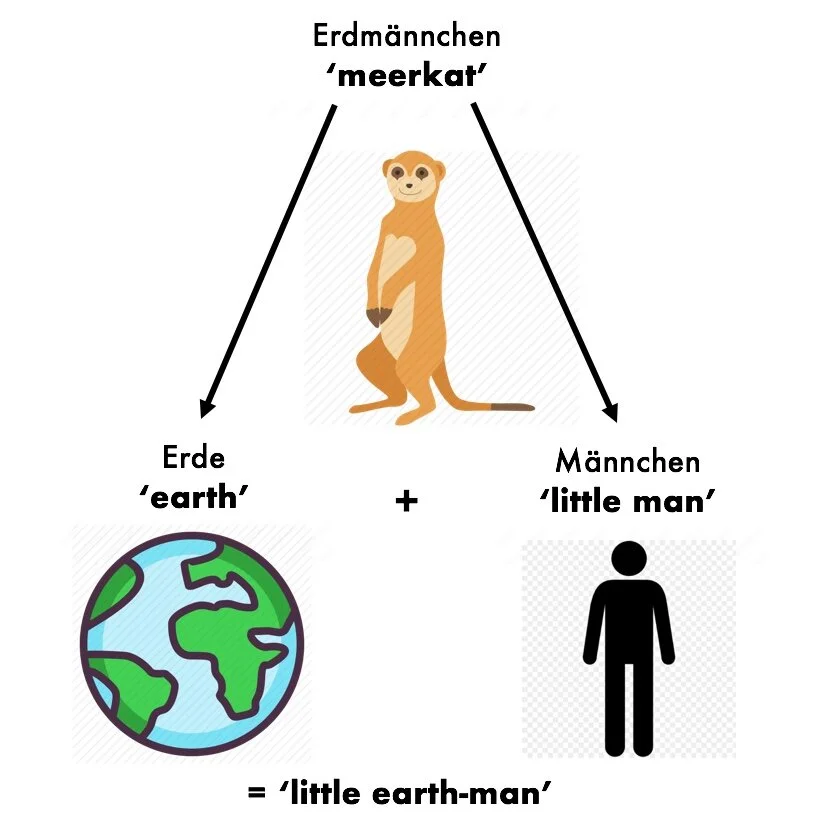

My father served in the US Army for most of the first two decades of my life, and some of his assignments were overseas. When I was aged three to six we were stationed in the Netherlands, and my earliest school days were spent in Dutch kindergarten and elementary school. (I’ve since forgotten most of the Dutch I learned, but at one time I used it for all interactions every school day. I remember clearly writing onto a PostIt note the first word I ever learned to write: the Dutch word aap, which means ‘ape’.) When I was 10 we moved to Germany, and for most of the next decade I attended German schools. In fact English was a compulsory subject for most of this time, so I had the pleasure of being, as a native speaker, taught English as a second language. The other languages I studied in this time (Latin and French being the big ones) were taught in German, just like all other school subjects.

Higher Education

My second year at college I took the linguistics intro course, and knew instantly that I had found my subject. The fascinating parallels I had observed and mused about for years -- between English, Dutch, and German, for instance, and between French and Latin -- came into much clearer focus as I learned about how modern linguists (in the sense of ‘language scholars’) think about language. I became fascinated by the thought of reconstructing languages of the past, especially the Indo-European language family, to which English belongs. In the late 1700s, European scholars well versed in European languages became aware of Persian and of the sacred language of India called Sanskrit. The word for ‘is’ is est in Latin and esti in Ancient Greek, so Persian ast and Sanskrit asti must have looked familiar to these scholars. They realized that what had thousands of years ago been a single speech community had broken up into several communities that lost touch with one another, allowing their language(s) to diverge. Over time the divergences multiplied and the regional varieties became mutually unintelligible. One thing that fascinates me about this realization is that, if one knows how to look for it, one can discern an underlying unity to superficial diversity.

MY SPECIALIZATIONS, EDUCATION, AND EXPERIENCE

I pursued a BA in linguistics, read everything on Indo-European I could get my hands on, and signed up for courses in Old English, Ancient Greek, and Sanskrit. Then when I graduated, I decided it was time to go in a new direction, so I moved to China to teach English as a second language (ESL). I threw myself into the study of the Chinese language and its rich writing system, the most complex one in use today. Though the character-based writing system and the tones of the spoken language are challenges to a learner coming from English, there is also a great degree of similarity in English and Mandarin syntax. Chinese has no inflection (this refers to certain types of variation in the forms of a word: for an extreme example of diversity in inflection, consider the fact that am, are, is, was, and were are all forms of the same English word, the verb be!), and while the language has ways of showing plurality or verb tense, such marking is largely optional in Chinese.

The Saga Continues

After my year in China, I taught ESL for about a year in Japan, and immersed myself in the study of that language. Japanese and Chinese are unrelated and largely dissimilar languages, but just as English has borrowed many thousands of words from French, Latin, and Greek in the last few centuries, Japanese speakers borrowed thousands and thousands of words from Chinese. They also borrowed the Chinese writing system along with these words, and found ways of using it to represent their own language. For example the word for ‘water’ is written 水, which is shui in Mandarin. In compound words that Japanese has borrowed from Chinese, this syllable is read as sui. But this same graph 水 is also used to represent the native Japanese word for water, mizu. Comparison of Japanese readings of Chinese words, as sui to shui in the example just given, soon became a fascination of mine. Most of the time the forms in the two languages will be quite close, but there is also much interesting divergence. For instance the word for ‘female, woman’ in Chinese is 女 nü, for which Japanese has 女 jo. The word for ‘two’ is 二 er, for which Japanese has 二 ni. These apparently arbitrary sound-correspondence patterns become clear when one studies older stages of the Chinese language.

My Work in Research

Several years after my time in China and Japan, I started work on a master’s degree in linguistics. During this time I joined a documentation project at UNT on the Lamkang language. Lamkang is spoken by about 10,000 people, primarily in the state of Manipur in northeast India. It belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family, meaning it is related to Chinese, as well as to Tibetan, Burmese, and hundreds of other languages of East Asia. Though the time of linguistic unity is thousands of years in the past, many words still show this archaic connection. For instance, the Lamkang word for ‘name’ is miing (as in k-miing ‘my name’, a-miing ‘your name’, and so on), which looks just like its Chinese cognate, 名 ming; compare also Tibetan word for ‘name’, which is མིང་ ming. Another example of related words is Lamkang bul which means ‘tree stem, base’, which has the same origin as Chinese 本 ben (same basic meaning). As so often happens, sound changes have occurred, and the original final -l has shifted to -n in Chinese.

Lamkang has only recently come to be written down: two translations of the New Testament have been published, as well as hymns and some word lists. But our understanding of the language is still in its early stages. Because the number of speakers is relatively small and there is great incentive for young speakers to shift toward using other languages (such as Manipuri, the state language, as well as Hindi and English), the language’s continued existence is far from assured. That is why we want to learn as much as we can about the language: some day in the future it may be gone, never to return. I had the great honor of contributing to the Lamkang documentation project for about seven years. My work mostly involved grammatical analysis of texts that had been collected, editing those texts and their translations, and trying to establish a spelling system. As someone who is interested in the Chinese language and its history, I’ve been especially fascinated by comparing the grammars of these two languages, and understanding Lamkang grammar has taught me a lot about how Chinese works.

WHY I LEARNED A SECOND/THIRD LANGUAGE

When I was in school, I learned a new language when my family moved to a new country: first Dutch, later German. In college, my main motivation to learn new languages was to understand the history of how related languages had diverged over time. After college, I sought to broaden my horizons by moving to China, a place where I did not know anyone, to start studying a language that had no historical connection to what I had learned until then.

I’ve never learned a language that I didn’t find absolutely beautiful. I appreciate both the unique sound that each language possesses as well as its grammatical structure and the rules by which speakers join words into sentences. The fact that essentially any thought can be uttered in any human language, and that each one does it in its own peculiar way, is mysterious and exciting to me. Figuring out how a language does what it does is like a puzzle, and who doesn’t enjoy puzzles?

Finding the Regular in the Irregular and the Unity in Diversity

Both as a learner and as a teacher, an abiding interest of mine is understanding how things within a given language came to be the way they are -- to see the regularity that hides beneath apparent irregularity. To return to that verb ‘to be’ I mentioned before, a learner of Modern English is confronted with am, is, are and told that these disparate words are really the same. With the knowledge one gains by comparing related languages and triangulating back to their common starting point, this kind of diversity can often be explained. Sanskrit, the classical language of India, has the same verb, as we saw above; and because we have records of this language from thousands of years ago, it takes us a good bit closer to the common source. ‘Is’ in Sanskrit is asti, while ‘am’ is asmi. From this comparison we see that the English word is has merely lost two sounds at the end, while am has lost the /s/ in the middle. But in the much older Sanskrit, this verb was quite regular: to the root as- are added suffixes -mi and -ti.

Language is, perhaps more than anything else, what makes us human. The more languages we learn, the more in touch we are with the rest of humanity.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!