Sense and Syllabicity, Part 2: Syllable Structure in Korean and German

Snow-covered Gyeongbok Palace 경복궁 in Seoul, South Korea. Source: RemoteLands.com.

THE SYLLABLE IN KOREAN

One language we touched on briefly in LanGoPod episode #3 is Korean, because syllable structure plays a central role in pronunciation. All Korean words and letters are shown in 한글 Hangeul (the native Korean writing system), alongside Revised Romanization (RR) in italics and with dashes (-) to denote syllable boundaries. Where needed, IPA symbols are included between square brackets.

Using “C” for consonants, “G” for glides, and “V” for vowels, the structure of the Modern Korean phonetic syllable can be represented like this:

(C) (G) V (C)

Note that speakers of some varieties of Korean may pronounce two consonant sounds in the coda for certain words, especially in careful speech, e.g. the verb 넓다 neop-da ‘be wide, spacious’ may be pronounced as it is spelled: neolp-da.

Vowels are the only obligatory part of a syllable and they only occupy one slot within a syllable: the nucleus. Optional elements of the syllable (shown in parentheses above) include one consonant and one glide in the onset slot, and one consonant in the coda slot. An example of a syllable consisting of only a vowel is 이 i ‘this’, and an example of a CVC syllable (shown in Fig. 1) is 힘 him ‘strength.’

Fig. 1. Example words showing the syllable structure of Korean.

In Modern Korean, glides may only precede the vowel, and there are only two such sounds, y and w. The glide w is written in Hangeul as a combination of either 오 o or 우 u with another vowel such as ㅏ a (to produce 와 wa) or ㅓ eo (to produce 워 wo). There is no independent symbol for y, however, and in Hangeul we simply double the short stroke of the vowel letter (as in the second syllable of 우유 u-yu ‘milk’). Fig. 1 also illustrates an example of a maximally full CGVC syllable, 관 gwan, which occurs in the word 관심 gwan-sim ‘interest.’

Let’s turn now to the 19 consonant phonemes (shown enclosed in curly brackets {}). Of these, two consonant letters have only a single sound value that remains stable whether they’re in onset or coda position: {ᄂ ᄆ n, m} (though we’ll see a special exception below for ᄂ). All the other consonants show variation that depends on their position within a spoken syllable. More phonetic contrasts are possible in the onset of a phonetic syllable than in the coda. Onset consonants can be:

plain {ᄀ ᄃ ᄇ ᄌ ᄉ g, d, b, j, s} — these have light aspiration when word-initial, and become voiced when the surrounding sounds are voiced;

(strongly) aspirated {ᄎ ᄏ ᄐ ᄑ ch, k, t, p} - these have strong aspiration when word-initial and we may also include {ᄒ h} in this set, though this is of course a fricative, not a stop; and

tense {ᄁ ᄄ ᄈ ᄊ ᄍ kk, tt, pp, ss, jj} - these are pronounced with a harder and stiffer voice (i.e. with the tongue, glottis, and diaphragm tensed) compared to their plain counterparts.

These phonetic distinctions between the plain, aspirated, and tense series are neutralized (i.e. no longer made) when the consonants are in the coda position of a phonetic syllable. As shown in Table 1, only the bilabial, alveolar, and velar stops ([p̚, t̚, k̚]) can occur in a Korean coda. Phonetic coda consonants cannot be tense. However, two of them, {ㅆ ㄲ ss, kk}, may appear at the bottom of a written syllable block. When they do, they are realized as [t̚, k̚], respectively.

Table 1. Phonetic contrasts between plain, aspirated, and tense Korean consonants neutralized in onset vs. coda position of the spoken syllable.

Note how many letters are pronounced [t̚] when the consonant stands in coda position!

An important point to note is that we must distinguish written syllable blocks (in Hangeul) from phonetic syllables, which refer to linguistic structure, independent of any writing system. The letter ᄋ represents the nasal consonant [ŋ] (ng) when written in the bottom of the syllable block, and in initial position shows that a syllable block has no initial consonant sound (called a “zero initial”). In the middle of a word (as in 상어 sang-eo ‘shark’) the consonant [ŋ] may form the onset of a phonetic syllable ([sʰa.ŋʌ] -- the dot marks the syllable boundary), but the letter ᄋ must appear in the coda position of the first syllable to represent this value so that it conforms to the rules of the written syllable block. *사어 would be sa-eo, with no consonant sound between vowels.

Finally, the letter ᄅ (r/l) has perhaps the most complex rules for determining the proper sound value. The basic value is [ɭ], a retroflex lateral liquid (RR: l). When it’s in the coda of a phonetic syllable it always has this value, as in 가을 (ga-eul) ‘fall.’ In onset position it’s generally replaced by the alveolar tap [ɾ] (RR: r), as in 이름 i-reum ‘name.’ But this replacement does NOT happen following a coda ᄅ (as in 빨리 ppal-li ‘quickly’) or a coda ᄀ (as in 격리 gyeok-li ‘quarantine’). Following coda letter {ᄂ n}, ᄅ retains its basic l value, and the n itself assimilates to [ɭ]. An example is the word 연락 ‘contact’: the Hangeul spelling is <yeon-lak>, but the pronunciation is yeol-lak.

Without an understanding of syllable structure, we as learners of Korean can easily feel overwhelmed by the diversity of sounds each consonant letter is associated with! Armed with the appropriate knowledge, however, we will be much better equipped to handle this diversity. Just remember that what is written as the coda of a syllable block will become the onset of a phonetic syllable when a vowel-initial syllable follows. For more tips on the pronunciation of Korean consonants, check out this post.

The Alexanderplatz Christmas Market in Berlin, Germany. Source: ToSomePlaceNew.com.

THE SYLLABLE IN GERMAN

German (like English) has a two-way distinction in stops and affricates based on the presence or absence of voicing, as opposed to the three-way phonation contrast in Korean. In German, too, there are several consonants whose pronunciation varies depending on their position within a phonetic syllable. The structure of the German syllable is can be represented like this:

(C) (C) (C) V (C) (C) (C) (C)

The vowel may be long or short. I don’t know of any single syllable that has all eight positions filled. Some that come close are strebst [ʃtʀeːpst] ‘(you) strive’ with a 3-consonant initial cluster (CCC-), and wirfst [vɪʀfst] ‘(you) throw’ with four consonants in the coda (-CCCC).

As in Korean, greater phonetic variety is found in the onset: here stop consonants may be (a) voiced or (b) voiceless aspirated, and fricatives may be voiced or voiceless. In coda position, however, German permits only voiceless sounds. Table 2 shows the onset and coda values for selected simple consonants in German.

Table 2: Onset and coda values of selected German simple consonants.

As German is a highly inflected language (meaning that nouns, adjectives, and verbs undergo modifications of form to show grammatical information), we can observe phonetic contrasts in the different forms of single words. Compare, from the word for ‘dog,’ nominative singular Hund [hʊnt] with plural Hunde [hʊn.də] -- here we see voiceless [t] syllable-finally, versus voiced [d] when a vowel follows. Nominative (abbreviated “nom.”) is the case in which a sentence’s subject appears, and note that all nouns in German are capitalized.

Similarly, in the word for ‘day,’ we find a voiceless final consonant in nom. singular Tag [tʰaːk], versus nom. plural Tage [tʰaː.gə] with a voiced stop.

This type of alternation is automatic for native speakers of German, meaning that they generally are unaware of it (unless they have linguistic training). They tend to carry this habit over into other languages, resulting in the well-known German accent which turns English “handbag” into “hantback.” Think of the band name Vulfpeck, which appears to be the word “wolf pack” as pronounced by a native German speaker.

As mentioned above, it’s not only stop consonants that show this type of alternation. The consonant spelled with a single <s> has multiple pronunciations that can generally be predicted based on the position in the syllable:

voiced [z] in syllable onset, whether at the beginning or in the middle of a word (summen [zʊm.m̩] ‘to hum,’ with a syllabic /m/, Häuser [hɔj.zɐ] ‘houses’);

voiceless [s] in syllable coda, whether in the middle or at the end of a word (Ausnahme [ʔaws.naː.mə] ‘exception,’ es [ɛs/eːs] ‘it’); and

voiceless palatal [ʃ] when in a cluster followed by [p, t] (Sprache [ʃpʀaː.xə] ‘language,’ Stimme [ʃtɪ.mə] ‘voice’), particularly in native words, less so in borrowed words. The 3-letter string <sch> represents the single sound [ʃ] (Schnee [ʃneː] ‘snow’).

An exception is found with loanwords, such as Sex (from English): [sɛks], contrasted with the numeral sechs [zɛks] ‘6.’ One onset cluster where <s> is pronounced as voiceless [s] is <sz> as in Szene [stseː.nə] ‘scene’ (a borrowing ultimately from Greek). The voiceless [s] sound does occur between vowels, but is spelled either <ss> as in Gasse ‘alleyway,’ or with the special character <ß> as in Straße ‘street.’ This written character arose as a contraction of “long S” <ſ> (used in earlier stages of English printing as well) and <z>. It never occurs at the beginning of a word.

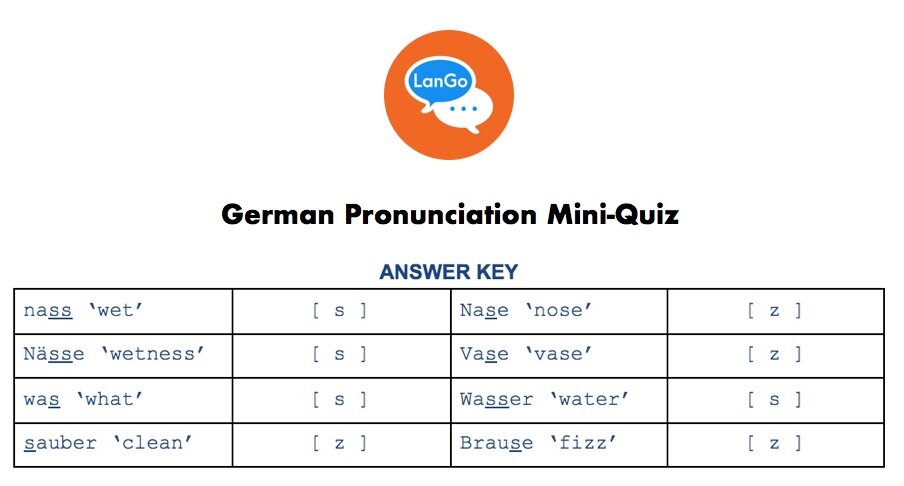

Put your knowledge of German syllable structure together by trying the pronunciation mini-quiz below! We’ve provided the answer key at the end of this post.

Finally, there is one German consonant letter whose pronunciation varies quite a bit depending on its position in a syllable, namely <r>. In an onset, most dialects of German have a voiced uvular trill [ʀ] (some have an alveolar trill [r] instead). The uvular trill is heard in French and Modern Hebrew as well, and is the sound we produce when gargling.

In a coda, this sound generally ceases to be produced as a true consonant, and instead we hear a low vowel [ɐ] (produced with the jaw just a bit higher than the [a] of English “father”). Consider two forms of the word for ‘gate,’ nom. singular Tor [tʰoɐ] versus nom. plural Tore [tʰo.ʀə].

I can think of one case where these sound values contrast in coda position: the pronoun ‘he’ (nom.) is er, with the vowel variant of /r/ [eɐ] (never [ɛʀ]), while the name of the letter <R,r> has the consonant sound [ɛʀ] (never [eɐ]).

As we saw above for Korean, a German consonant’s position within a phonetic syllable has important consequences for its correct pronunciation. In order to overcome the habits of our native languages it is very important to observe these distinctions made by speakers of our target languages. Syllable, onset, and coda are thus very valuable concepts to be aware of as we observe, make generalizations, and learn to adjust our speech habits in acquiring a new language.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!