Eat, Kick, Bite: Transitivity for the Language Learner

Introduction

In this blog we discuss transitivity, which was the topic of LanGoPod episode #6. Transitivity is an important and useful notion for language learning. Most languages have at least some phenomena which interact with transitivity. Transitivity is a property of a clause and refers to the number of core arguments that the clause contains. An intransitive clause contains one core argument, a transitive clause contains two, and a ditransitive clause three core arguments. Believe it or not, these are the three basic sentence types for every sentence in every language in the world!

Clauses and core arguments

Recall from LanGoPod ep. #5 and its accompanying blog post, that a phrase is made up of a word or words. A clause is made up of phrases. Typically, a clause has at least a noun phrase and a verb phrase, and as we suggested at the end of LanGoPod Blog #5, a clause also includes an inflectional or tense phrase. Basic sentences typically consist of a single clause. (A more complicated sentence may have multiple clauses, but that is a topic for a future post.)

A noun phrases within a clause can be classified as either a core argument or a non-core argument. An argument, in the study of syntax, refers to the noun phrases that are the main participants and make up the core meaning of a sentence or clause. Core arguments are essential to the interpretation of the clause, and they contribute to the transitivity of the clause. On the other hand, non-core arguments do not contribute to the transitivity of the clause.

It is worth noting that a core argument may be omitted from the “surface form” of the clause in certain languages, such as in Japanese and Korean. However, even if they are not pronounced, core arguments are still recoverable from the context, and they still contribute to the overall transitivity of the clause. In languages like Japanese and Korean, it is therefore important to learn about transitivity, as there is are series of verbs which bear different forms depending on the transitivity of the clause! Stay tuned for a forthcoming blog post that looks at how transitivity works in these languages.

Transitivity

Learning the grammar of a new language can seem overwhelming at times. Did you believe me when I told you there are only three types of basic sentences? It’s true! There are basic clauses with a single core argument, basic clauses with two, and basic clauses with three core arguments. That’s it! Even very complicated sentences which contain multiple embedded or dependent clauses can be categorized by their number of core arguments, and all of their internal clauses can also be categorized this way.

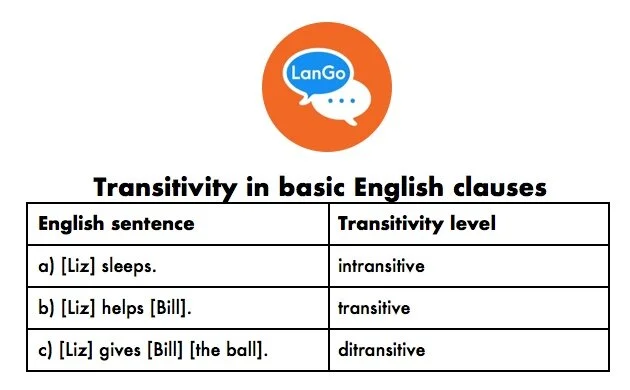

We can correlate the number of core arguments in a clause with the clause’s overall transitivity. (By the way, note that transitivity in linguistics is distinct from the concept of the same name in mathematics.) Put simply, a clause with a single core argument is classified as intransitive, a clause with two core arguments is transitive, and a clause with three core arguments is ditransitive. Table 1 illustrates the different levels of transitivity with three basic English clauses.

Table 1: Transitivity in basic English clauses.

Linguists have written a plethora of literature on the topic of transitivity, and they don’t all agree. One notable point of controversy is whether transitivity is a property of verbs, or of clauses. In this blog post, we treat it as a property of clauses, in line with the majority consensus.

It is important to point out that there is great variation in transitivity across various languages. Linguists observe that things that are transitive in one language might be intransitive in another. Furthermore, there are parts of a language's grammar that may not neatly fit into a binary, “either/or” view of transitivity. Linguists Paul Hopper and Sandra Thompson (1980) list several semantic considerations that help to explain why distinct levels of transitivity are observed to break down at certain parts of the grammar across different languages. Nonetheless, levels of transitivity are largely treated as neat and distinct in this blogpost because a strict view of transitivity is very useful for language learning. When a language learner eventually encounters an area of fuzzy transitivity in their target language, they will be better able to understand what’s going on having started off with a strict, simplified view of levels of transitivity.

Transitivity and prepositions in English

Recall that transitivity strictly correlates with the number of core arguments in a clause. We can examine levels of transitivity in English by first establishing a diagnostic for what counts as a core and what as a non-core argument.

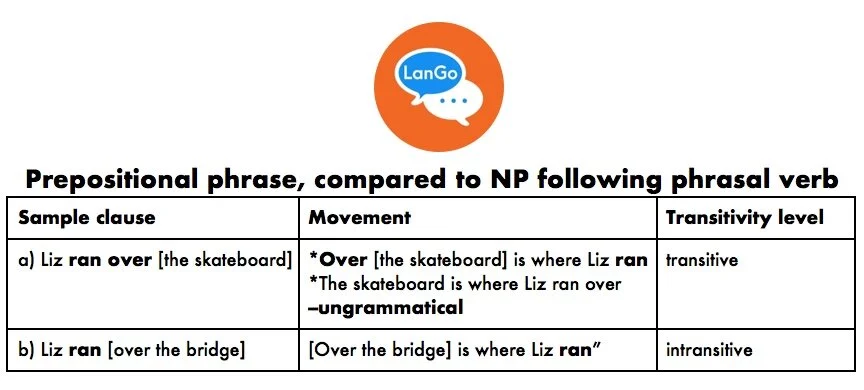

There are multiple types of non-core argument in syntax, but for now we will focus merely on distinguishing core from non-core. In English, it seems that core arguments are both essential to the interpretation of the clause and that they are never headed by a preposition. The only time a core argument may be preceded by a preposition is if the preposition is not actually part of the noun phrase. For example, an object noun phrase may follow a phrasal verb that ends in a particle, such as “at”, which is also used as a preposition elsewhere in the grammar. Table 2 illustrates this distinction.

Table 2: Prepositional phrase, compared to NP following phrasal verb.

Recall that we can test whether an element is a constituent with the noun phrase through movement! In Table 2, the verb in the sample clause is in boldface, and the constituent is in square brackets. Clause a) is transitive, even though a preposition (apparently) precedes the noun phrase “the skateboard.” We can tell that “the skateboard” is a core argument because our movement test shows that the preposition “over” is actually part of the verb phrase “ran over,” not the head of a prepositional phrase. The movement test in clause b), however, shows that “over the bridge” is indeed a constituent, and thus “the bridge” is not a core argument. Since a) has two core arguments it is classified as transitive, but b) only has a single core argument and is therefore intransitive.

We’ve looked at the distinction between phrasal verbs and verbs followed by a prepositional phrase. We learned that a clause which semantically has two participants may vary in transitivity depending on whether the second participant noun phrase is headed by a preposition.

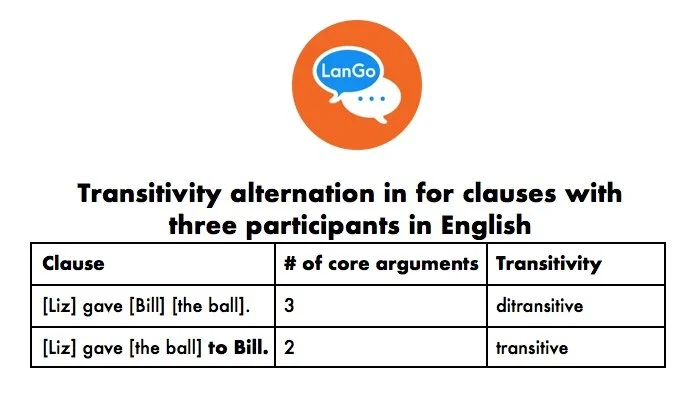

Now let us consider events of transfer such as “giving,” which have three semantic participants but may be either transitive or ditransitive, depending on how many of the participants are core arguments. Table 3 illustrates the alternations in transitivity for clauses with three participants. Note that the core arguments are in square brackets and the prepositional phrases are in bold.

Table 3: transitivity alternation in for clauses with three participants in English.

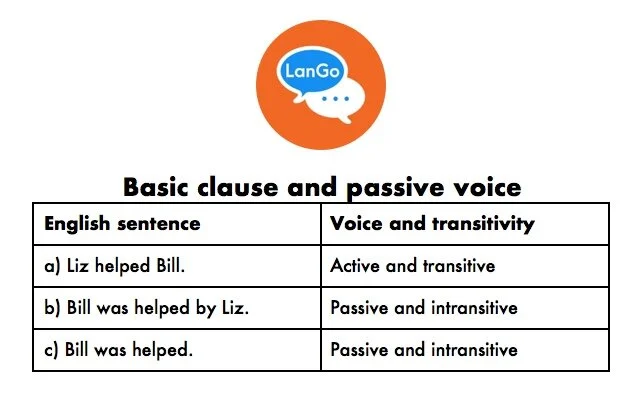

Does the alternation in transitivity observed in Table 3 make any difference in the grammar? Yes it does! The difference becomes more clear when we convert the clauses into passive voice.

The basic clause, as we have presented it here in this post, can be considered to be in the active voice. If we view the passive voice as a transformation of a basic clause in active voice, then we can see that the passive voice reduces the transitivity of a basic clause by making the subject of the basic clause a non-core argument in the passive clause. The non-core participant in the passive voice may have been the subject of a basic clause, but in the passive voice it is preceded by a prepositional phrase and thus optional for the interpretation of the clause (see Table 4).

Table 4: Basic clause and passive voice.

Linguists can confirm the transitivity level of a passive voice construction through a series of formal syntactic diagnostics, but it is enough for the language learner to understand that using the passive voice amounts to a reduction in transitivity compared to using the active-voice counterpart. For curious readers interested in learning more about how formal syntax can investigate transitivity, please contact LanGo for private lesson consultation.

Summary

This blog post has focused on explaining the notion of transitivity and pointing out how similar-looking clauses in English may differ in transitivity. The notion of transitivity is crucial to the production and perception of voice alterations, such as the ones we examined in English. However, transitivity interacts with other parts of the grammar in English and other languages. Equipped with this knowledge, a vigilant learner will be able to spot transitivity in many aspects of the grammar of their target language!

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!