Verbos Irregulares

Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, Mexico. 📸: Lucas Vallecillos, VWPICS/REDUX.

Learning the Spanish verb paradigm is an enormous task to wrap one’s head around, and it is perhaps the most complicated thing any learner of Spanish encounters. This post is intended to help people who have some familiarity with Spanish verb conjugations, but still find themselves scratching their heads when it comes to irregular verbs.

There are basically two types of verbs in Spanish, and they take slightly different suffixes.

The two types are called -ar verbs and -er/-ir verbs, so named because their infinitives either end in -ar (as in manejar ‘to drive’) or in -er or -ir (as in comer ‘to eat’ and escribir ‘to write’).

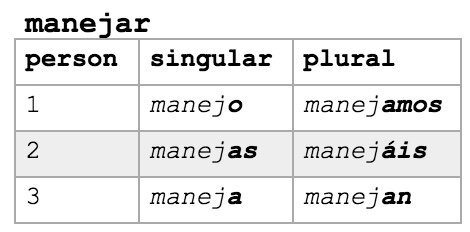

Except in the preterite (simple past), Spanish verbs mostly take the same basic suffixes. Table 1 shows the set of singular and plural suffixes that -ar verbs take for first, second, and third person in the present tense.

Table 1: The verb manejar ‘to drive’, present tense, with suffixes bolded. Note: the second person plural form is the one that goes with vosotros ‘y’all’, which is only used in Spain. It is included here for completeness.

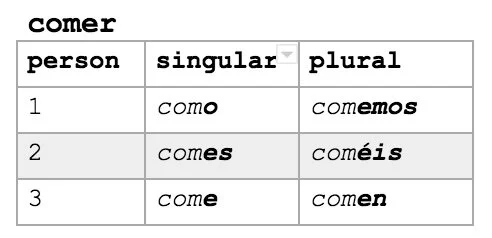

Verbs ending with -er and -ir can be placed in the same category, because they basically behave in the same way, i.e., they take the same set of suffixes, as shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2: The verb comer ‘to eat’, present tense, with suffixes bolded.

But often, other suffixes come before these suffixes to convey information such as tense, aspect, or mood. This is grammatical information that encodes meanings such as the time of the action and how long it lasted. These suffixes take slightly different forms for -ar verbs and -er/-ir verbs.

Many verbs are perfectly regular, and therefore behave in predictable and rule-based ways that can be neatly summed up in a chart with no peculiarities.

There are many other verbs, however, that behave in ways that are different from the predictable pattern, and these verbs are called “irregular”. But are they truly irregular, meaning ‘not governed by rules’? In this blog post, I address three types of so-called irregular verbs, show their underlying patterns, and outline some rules which describe their behavior. These types, I call: spelling changes, stem vowel changes, and -cer & -cir verbs.

Spelling Changes

Let us first look at one type of verbos irregulares, which, spoiler alert, I believe are placed in the irregular category by mistake.

An example of this would be buscar ‘to look for’. Let us look at the alleged irregularity of this verb in Tables 3 and 4, which illustrate preterite and subjunctive forms (respectively) of the verb buscar. These are among the only times that an -ar verb like buscar occurs with a suffix beginning with the letter <e>.

Table 3: Preterite forms of buscar ‘to look for’, with IPA.

Table 4: Present Subjunctive forms of buscar ‘to look’.

According to our rules, we should take off the infinitive suffix -ar, and attach our suffixes. However, attaching this suffix seems to defy our expectations. There is a <qu> here, but there’s no <qu> in our root. So what the heck? Why does it have a <qu>? It’s so irregular!

If we write the root of this verb out phonetically, using the IPA, we get [busk-]. The suffix of [-é] is the perfectly regular thing to do. This should yield the form [busˈke]. The little mark there(ˈ) is the IPA’s way of indicating stress. But when you try to put this suffix onto the root in the spelling <busc +e>, you get the incorrect form busce, which would be pronounced [buˈse], and [busˈθe] in Spain. So we need to change the spelling in order to show the intended sound [k]. We need a way to represent the syllable [ke], and the way we do that in Spanish is with the letters <que>. A sound [k] is always represented as <qu> when it comes before an [e] or an [i], and as <c> elsewhere, unless it's a foreign word or name. So as we can see, these verbs are not actually irregular. They are following the rule (suffixation) exactly as a regular verb would do and just have to undergo a systematic spelling change in order to make that happen.

Now there is not just <c> changing to <qu>. There is another symmetrical change that occurs with the letter <g>.

Let’s take a look at the verb llegar ‘to arrive’ in the preterite in Tables 5 and 6, which illustrate preterite and subjunctive forms (respectively) of the verb llegar. These are among the only times that an -ar verb like llegar occurs with a suffix beginning with the letter <e>.

Table 5: Preterite forms of llegar ‘to arrive’, with IPA. <Ll> is represented as [ʒ] here, but other possibilities for this sound are [ʎ] or [ʝ] depending on the dialect!

and in the present subjunctive:

Table 6: Present Subjunctive forms of llegar ‘to arrive’.

Again, we get this <u> apparently out of nowhere—what the heck? But if we were to omit the <u>, the letter <g> would have the sound of <j> [x], as in the word gente [xente] ‘people’. Again, if we want to write [ʒege], we will need to add a silent letter <u> before <e> and <i>: llegue. Otherwise it would be llege [ʒexe], which is not a word.

These are predictable patterns if you know the rules of Spanish spelling. In fact, I will go so far as to make a prediction about them. This specific sort of alleged irregularity (adding <u>, or changing <c> to <qu>) will only occur with -ar verbs whose stems end in the letters <g> and <c>, and you will never find an -er verb with a <c> final root changing to <qu>.

Stem-vowel changers

Now let’s look at a stem-vowel-changing verb like encontrar ‘to find’. Now this group of verbs follow rules that are more substantial than just spelling changes, but they are not so chaotic that we can’t make sense of them.

Do you remember the stress rule of Spanish? Always stress the second-to-last syllable (example: brazo ‘arm’), unless the final syllable ends in a consonant other than [n] or [s] (example: genial ‘great’), in which case stress that syllable instead. Any exceptions to this rule explicitly mark the accented syllable with an acute accent, called the tilde in Spanish (example: the initial <u> in útil ‘useful’).

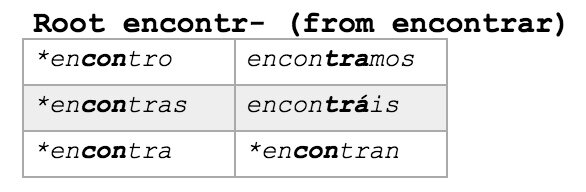

Now imagine we just add our suffixes to the root to get our forms. In Table 7, we will encounter the verb encontrar ‘to find’. Notice where the stresses (in boldface) are in Table 7; the asterisk preceding a word shows that it is incorrect as those marked with *, require an additional step, discussed in the next paragraph.

Table 7: root encontr- (from encontrar ‘to find’) with present tense suffixes added and stresses marked.

Now, every time the stress falls on the syllable -con- of encontrar, it becomes -cuen-. In all other cases, it stays -con-.

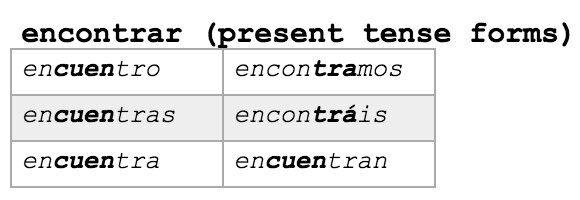

Now view the real paradigm in Table 8:

Table 8: Present tense of encontrar ‘to find’.

This o to ue change is true throughout the entire chart for most stem-vowel-changing verbs. Just as we saw a change of o -> ue, similarly, in the verb empezar ‘to begin’, we see a change of e -> ie. Examples of this change include: empiezo ‘I begin’ and tiene ‘he/she/it has’, from tener, ‘to have’.

-cer and -cir verbs

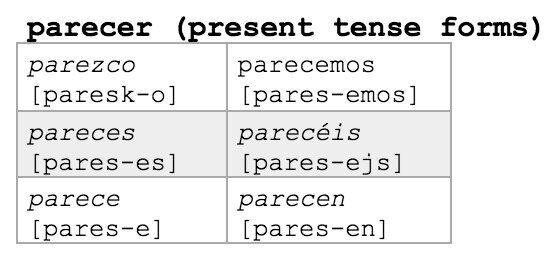

Another type of irregularity happens in verbs whose infinitive forms end with -cer or -cir. They are believed to have a <z> that comes out of nowhere. For example, look at the conjugation of parecer, ‘to seem’, in the present tense, in Table 9:

Table 9: Present forms of parecer ‘to seem’, with IPA (Latin American pron.).

Look at that <z>. Isn’t it peculiar? My question to the reader is “What could possibly be the root of this verb?” If the root is <parec->, how does that <z> get in there? This phenomenon can be explained with a root that is underlyingly <parezc->. Try applying the suffixes as shown in the paradigm of Table 10:

Table 10: Hypothetical Present forms of parecer ‘to seem’ (*parezc-er), without spelling redundancies fixed

Now if you pronounce these word forms, you will find it exactly correct. However, the <z> and the <c> (with an <i> or an <e> following) have the same sound, so the letter <z> is deleted in all places where it is not needed. The correct forms are shown in Table 11.

Table 11: Actual present forms of parecer ‘to seem’, with accurate spellings.

Conclusion

In this blog post, I have not provided a comprehensive list of all of the things that happen in “irregular” verbs, but hopefully I have given you a taste of the ordered patterns found in this group of verbs, even while they are typically regarded as aberrant or unusual in some way.

Whenever I get confused about a verb form, I go to the app SpanishDict, which is a great dictionary. It has the most complete list of verb forms and tenses I have yet found. With more forms than the book 501 Spanish Verbs, which lists 14 tenses, SpanishDict seems to have 24 forms of each verb, from indicative to subjunctive, progressive to preterite. Another great way to learn Spanish is to come to LanGo, where we have Spanish classes each week!

So go forth and use as many verbos irregulares as you can, and be comfortable in the knowledge that they are systematic too!

![Table 5: Preterite forms of llegar ‘to arrive’, with IPA. <Ll> is represented as [ʒ] here, but other possibilities for this sound are [ʎ] or [ʝ] depending on the dialect!](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bb3b241e8ba44ae9c39e05b/1586269775860-WWIU9TSHDOPC1B3GY5I7/table.jpeg)

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!