A Chinese Alphabet: Qwerty to Hànzì

Dear reader,

Are you curious about Chinese writing, but find it a bit daunting? Have you ever wished you could just look at an unfamiliar Chinese character and input it, without needing to have memorized its reading or its meaning?

If so, then today’s post is for you! It introduces a wonderful Chinese character input system called 倉頡 Cāngjié. Note that the letter <C> indicates the sounds [ts]. It’s named after the legendary four-eyed inventor of writing in China. Using the 26 keys of the Qwerty keyboard, we can input Chinese characters (and punctuation) by breaking them down into their constituent parts. In this system there are 24 basic characters, and all the thousands of others are treated as combinations of these elements. Chinese characters, 漢字 (simplified 汉字), are known by many names: “Sinograms” (from the Greek name of China), “Hànzì” (from Mandarin), “Hanja” (from Korean 한자), and “Kanji” (from Japanese かんじ). Whatever you prefer to call them, they are the most complex writing system in use today.

One of my absolute favorite features of the Cāngjié input system, as opposed to others that I’ve learned, is that Cāngjié lets us input and look up characters that we have never encountered before! What this means is that it’s not tied to any particular language or dialect in the way phonetic input systems are. Therefore I hope that this post will be useful not just to learners of Standard Chinese, but also to students of other dialects, as well as students of Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and to anyone interested in reading, using, or just knowing more about Chinese characters. (Which, who wouldn’t?)

Step 1: THE BASIC TWENTY-FOUR

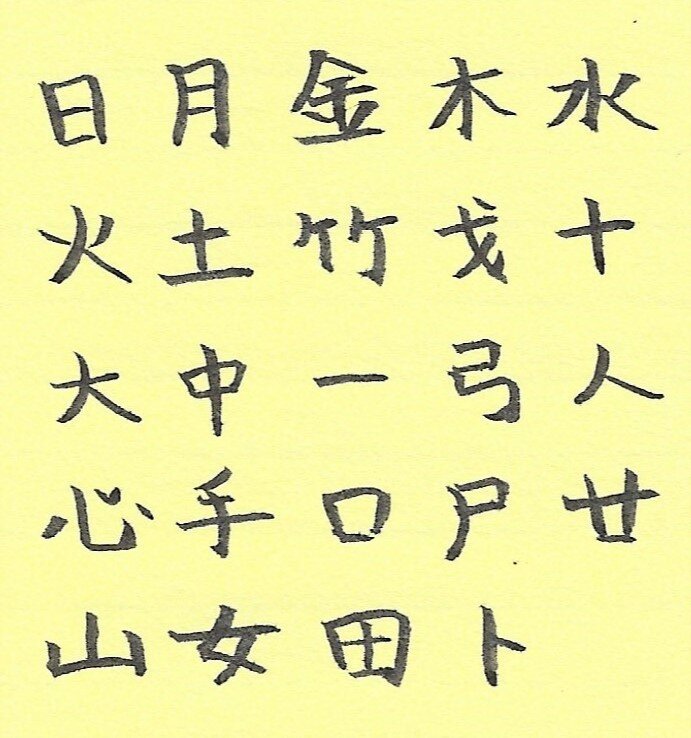

Table 1 introduces the system’s 24 basic characters (letters X and Z have special uses that we won’t cover in this post), as well as some custom mnemonic prompts to help you associate each keyboard key with its Chinese character shapes. There are keyboards with these basic characters printed on the keys, as well as stickers you can affix to your keyboard. However, if you’re able to memorize these pairings, you won’t need to be reliant on specific hardware.

TABLE 1: Basic letter-to-character correspondences.

(The last mnemonic plays on the Mandarin reading of 卜, bǔ, and the lookalike Japanese phonetic symbol ト /to/.)

Another thing I hope will help your memory is to note cases where Roman (or English) letter shapes are similar to certain character forms:

within 戈, look for the lowercase <i> being knocked off balance.

大 rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise resembles <K>.

an important variant of 中, <⼁>, is like a lowercase <l>.

廿 recalls two lowercase <t>’s.

removing the central stroke from 山 leaves <⼐>, essentially the shape of <U,u>.

the stroke within 女 that reaches from top to bottom (く) is a rotated angled stroke like <V>.

卜 can be viewed as an upside-down <Y>.

Step 2: VARIANT FORMS

In the paragraph above we saw a few variant forms related to the basic 24 character forms (⼁ from 中, ⼐ from 山). Recognizing such variants is an essential part of using Cāngjié input! Many variants are straightforwardly related to the basic characters, but a few are unexpected. I’ve arranged most of the important variant forms into Table 2 to make the relationships clear.

Many Chinese characters have combining forms distinct from their basic absolute forms (see this blog post for more); these are shown here in column (a). In my view, all other Cangjie variants are derived by 5 distinct processes (columns (b) through (f)), while column (g) shows a few variants that seem arbitrary. Some variants are derived by two steps, and these are shown here in secondary rows headed by lowercase letters.

TABLE 2: Variant forms associated with the basic 24 characters.

Overview: TWO-PART COMBINATIONS

Here is a spreadsheet showing all characters that the Cāngjié system breaks into two components: each first component gets its own row, and each second component its own column. Several cells have more than one character, as these are treated by the Cāngjié system as having the same components in the same order.

Let’s consider some characters in Row C of the spreadsheet, meaning those with the first component 金 (Gold). In the first few characters we can clearly see the same basic form on the left side: 鈤 鈅 鈥 釷. In Column I, however, we find 公, which lacks 金. Instead it has the upper portion ハ, which is a subtractive variant of Gold (see column (c) in Table 2 above). By “subtractive variant” I mean that the form is derived by leaving out certain strokes of the basic character. Looking a bit further in the Gold row of the spreadsheet, in Column K we find a cell with the two characters 父 釱. Here again we find the variant ハ in the first, versus the full form 金 in the second. The second component of both of these is, in the Cāngjié system, 大: in 釱 we see the basic shape, while 父 has the subtractive variant 乂.

How the system works: THE HUNDRED NAMES

The Hundred Names (百家姓) is a famous rhyming poem incorporating the most common Chinese surnames. Some names have become homophones in recent centuries, such as 張 and 章, both pronounced “Zhāng” in Mandarin, so referring to this poem is a useful way to distinguish such soundalikes. If you want to master reading Chinese, learning this poem will be a great help in recognizing names: unlike European languages, written Chinese uses neither capital letters nor word spaces to show where a name begins and ends!

Here, just to get a sense of how Cāngjié works, we’ll take a look at the first four names which form the first half-line of the poem.

Cāngjié components are read off the character from top to bottom and left to right (depending on the structure of the character). Note that the hyphen is not a part of Cāngjié input; I include it to help learners recognize the most important boundary between character components. The spellings of the surnames here are limited to the standard spellings in Hanyu Pinyin and the Revised Romanization of Korean. In actual practice many, many variant spellings of names exist: the fourth name, 李, for example, is also Romanized as “Lee,” “Rhee,” “Yi,” and so on.

TABLE 3: The first four surnames in 百家姓, ‘The Hundred Names’.

Step 3: RULES OF ORDER

As we’ve seen in this post, the components of a character are read either from top to bottom or from left to right, depending on the structure of the character. This order agrees with that of components as we write them by hand. (Keeping the stroke order constant is very important in mastering calligraphy!)

There is a third order, aside from downward and rightward, which is a bit rarer than these two: from outside in. Some characters have enclosures, in which case the inside is specified last. For example:

圓 is made up of the enclosure 囗 surrounding 員. (Note that, though they both appear as squares, the enclosure 囗 is distinct from the Mouth 口 <r>. The Mouth component never has anything inside it.)

To input 圓, we type <w> to represent 囗, followed by <rbuc> for the 員 on the inside. In handwriting, the surrounding component is broken up: first we would write three of the four sides, ⼌ (in two strokes), and the ‘floor’ (bottom stroke of the enclosure) is added last of all.

For those of you who already have experience writing Chinese characters, note that there are cases where the Cāngjié input order differs from the standard stroke order. Radical 162 ⻌, as seen in 道, is hand-written as the final component, but as Cāngjié reads components strictly from left to right, and never right to left, it uses <y> preceding the other strokes. 道 is thus entered as <ythu>. Another example is the simpler character 方, where the downward stroke ノ <h> is to hand-written last; but since it’s to the left of the <s> stroke, the overall Cāngjié keystroke order is <yhs>.

Step 4: RULES OF ABBREVIATION

A very important feature of Cāngjié is that the maximum number of keystrokes is five. There are, however, many characters with more than five components.

How does Cāngjié accommodate such cases? Recall how we enter the 走 component <gyo> above in the name 趙 <gofb>—we abbreviate! As a rule we keep the first and last components when we abbreviate, and leave out the middle.

Let’s examine the various ways the character (or component) 言 ‘speech, language’ is encoded in Cāngjié. (1) As a standalone character, all parts are encoded, and we read from top to bottom: (a) ⼇, variant of <y> 卜; (b) two horizaontal strokes follow, <mm> 一一; and at the bottom is the Mouth 口 <r>. So the sequence keystrokes is <ymmr>.

This component 言 sometimes occurs on the bottom of characters, as in 警 ‘warn, be alert.’ The top part (敬) is abbreviated, so we enter just its first and last components, <tk>. Recall that five keystrokes is the maximum, so we’re left with three keystrokes to enter the 言 on the bottom of 警. So instead of <ymmr>, we drop one of the horizontal strokes: <ymr>. The keystrokes for 警 thus are <tkymr> (rather than the fully-spelled-out *tpr-ok-ymmr, with nine components).

But 言 is much more frequent as a left-side component, as in 語 ‘language.’ In cases like this we omit the other horizontal stroke and input just <yr> for 言. This leaves three keystrokes to represent the right side, 吾. Here too we abbreviate: <mmr> (instead of the full <mdmr> we might expect). Thus the input string for 語 is <yrmmr>.

CONCLUSION

Mastering Cāngjié input takes a bit of practice, even if you are already proficient in reading and writing Chinese characters. But I encourage you to give it a try: once you get started it feels very much like a game, and getting the components right becomes rewarding. I particularly recommend the virtual keyboard linked to at the top of this post: you get to see characters being built up as you enter them, and it auto-predicts your next strokes. This makes it a very useful tool for learners.

For reference I leave you with the table below of basic character shapes organized by the number of strokes. Good luck in all your studies, and please check out the other posts on the LanGo Blog!

TABLE 4: Basic character shapes organized by the number of strokes.

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!