‘More-Than’ Words

Introduction

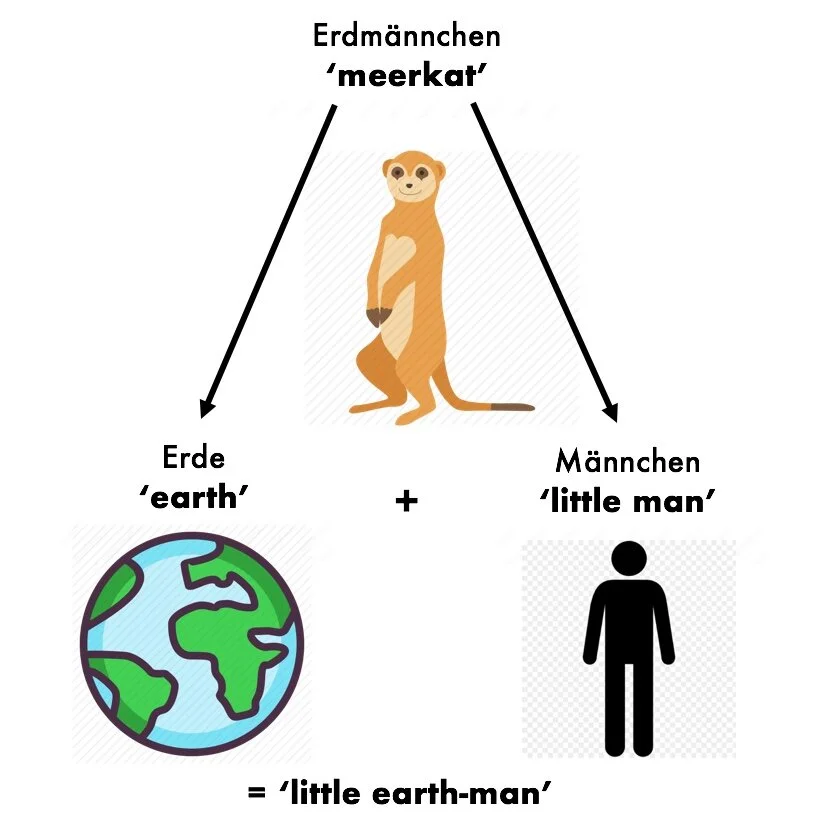

Most words are just words and can easily be assigned to a particular part of speech. Some words are compounds, meaning they’re made by sticking together two or more smaller words, like “housefly”. Then there are blends (also called “portmanteau words”) which are also put together from existing words, but where the boundary has been blurred: “smog”, “brunch” and “guestimate” are well-known examples.

But then there are cases where two or more words, usually belonging to distinct parts of speech and frequently co-occurring in unstressed parts of a phrase, have become smooshed together so thoroughly that speakers stop perceiving them as distinct words. For example, Modern English has the verbs “don” and “doff” (recall the line “Don we now our gay apparel” from “Deck the Halls”). They mean ‘put on’ and ‘take off (clothes)’, respectively. They originated from a smooshing together of the verb “do” with the particles “on” and “off”. Note that the past-tense forms are “donned” and “doffed” (and not *did-on, *did-off). Once people started to use these past-tense forms with the regular -ed suffix, we can deduce that these fusions had the status of single words rather than 2-word collocations.

What these fusion words show, alongside compounds and blends, is a kind of arithmetic peculiar to languages: 1 + 1 = 1. When one word fuses with another, the result is a single unitary word. To us as language learners, it’s important to (a) recognize these fusion words when we hear and see them, and to relate them to their constituent parts (which will help us remember their meanings); (b) produce them correctly and idiomatically (see the discussion of the French fusion words du and au below); and (c) know whether fusing words into a single form is optional or obligatory.

With a hat-tip to the band Extreme and their 1990 hit song, here’s a short survey of what I’ll call “More-Than Words.”

Fusion Words in English

One very important set of this type of words is negatives: these arose from fusion of the Old English negative marker ne with words that followed:

never, neither, nor

The second component in each case has survived into Modern English:

ever, either, or

In fact, in the first example, “never”, we can still replace the fusion word with an equivalent 2-word phrase:

never = not + ever

We can’t replace “nor” with “not or” in Modern English; for “neither”, however. Compare these two equivalent sentences:

She didn’t go, and neither did he.

She didn’t go, and he didn’t, either

This demonstrates that “neither” is logically equal to “not either”.

In fact the Modern English word “not” results from fusion too: it originated in the Old English phrase ne + ōwiht, or ne + āwiht, which consisted of the negative particle ne, the adverb ā ‘ever’, and the noun wiht (which survives as “wight”, a now archaic word meaning ‘living creature’) — the meaning was roughly ‘never a thing’. Related English words are “nought” and “naught” (the latter form is the source of the more common word “naughty”), which both come from Old English na wiht ‘no thing’.

Interesting parallels in other languages include the French two-part negation ne … pas, originally meaning ‘not a step’, and the Ancient Greek negative particle ou (also ouk or oukh), thought to descend from a phrase meaning ‘not on your life’. “Utopia”, a word created by Thomas More for his 1516 book, is made from this ou + the word topos ‘place’: “No-Place”.

A further fusion word from Old English ne survives only in the collocation “willy-nilly”: the verbs involved are “will” and its negative “nill”. The expression may have come from several phrases:

will I, nill I: ‘if I am willing, if I am not willing’

will ye, nill ye: ‘if you are willing, if you are not willing’

will he, nill he: ‘if he is willing, if he is not willing’

The unstressed pronouns in all of these phrases were phonetically reduced to just the vowel [i].

A Modern English fusion word not involving the negative is “though”: it is taken from Old Norse þó (pronounced like “though” but likely with a voiceless [θ] initially; the letter þ representing this is called Thorn), which represents a fusion of the Indo-European *to- demonstrative stem (seen in the words “the”, “there”, “thus” and others) with the particle *kʷe which meant ‘and’.

IE *to+kʷe → Germanic *þauh → Old Norse þó

Fusion Words in German

Modern German has several frequently-occurring fusional forms of prepositions + certain forms of the definite article meaning ‘the’ (namely the accusative singular neuter das, or the dative singular, masculine or neuter dem). These fused forms include:

am, ans — with the preposition an meaning ‘on, at, to,’ etc.

an + dem = am

an + das = ans

im, ins — with the preposition in meaning ‘in, into’

in + dem = im

in + das = ins

vom, zum — the prepositions von ‘from, of’ and zu ‘to, toward’ here occur only with the dative case, so there can be no forms xvons, xzus.

von + dem = vom

zu + dem = zum

Note that while the final -s of das is added onto the end of the preposition, the final -m of dem takes the place of the final -n of an, in, von (while it is simply added to the end of zu).

Most of the time fusion of preposition + article into a single word is optional, but sometimes it is obligatory: to say ‘for example’ we must say zum Beispiel, we cannot say xzu dem Beispiel, even though zum and zu dem are logically equivalent. (If this seems odd, consider that in English greetings, such fusions or contractions are also often obligatory: we say “What’s up?” but never x“What is up?” We say “How’s it goin’?”, but I’d bet you’ll never hear x“How is it going?” as a greeting.) When we want to emphasize the definite article by placing stress on it, fusion cannot occur. For instance, to say ‘In this case it was so, but not in that one,’ we might say:

In dem Fall ja, aber nicht im anderen.

In the first phrase, when we’re stressing the word dem, we could not have im instead; but at the end of the sentence, we could use either in dem or im.

In Standard German, this type of fusion is limited to certain prepositions; not all prepositions fuse with an article. Combinations such as xmim (from mit + dem ‘with the’) and xohnes (ohne + das ‘without the’) are conceivable, and may be heard in dialectal speech, but you will not encounter them in writing.

Fusion Words in Latin

Like Old English, Latin had many words derived from fusion with a negative particle, which in Latin also had the form ne (these words are cognates, as Old English and Latin are related languages). Examples include:

nemo ‘no one’, from Old Latin ne hemo (hemo is equivalent to Classical Latin homo ‘person, human being’, as in “homo sapiens”, and the source of French homme, Spanish hombre)

ne + hemo = nemo

neuter ‘neither’, from ne uter ‘not either’ — English has “neuter” as a verb, and related words are “neutral” and “neutrality”

ne + uter = neuter

nolle, a verb meaning ‘not to want’; it comes from a contraction of ne and velle ‘to want’ and occurs in the well-known phrase noli me tangere (‘touch me not’ — literally ‘you don’t want to touch me’, John 20:17)

ne + velle = nolle

The verb velle has another fused derivative, namely malle ‘to want more, rather’, where the first element is magis ‘more’. This is also the first element in the words maior ‘greater’ (source of English “major” and “majority”) and maximus ‘greatest’ (from which we get “maximum”, the neuter form).

The English words “possible” and “posse” derive from a fused verb posse ‘to be able, can’. The first element here is the Indo-European word *poti- meaning ‘lord, master’ (seen also in “despot”, from Greek, and in Sanskrit pati ‘husband, lord, master, owner’), and the second is the copula esse ‘to be’. So this verb meaning ‘be able’ originally meant something like ‘to be the master’!

*poti + esse = posse

There are several other Latin verb stems that arose through fusion of what were previously distinct words. Some are fusions of verbs with prepositions:

debere ‘to owe, to keep from someone’, whose components are de ‘from, away, off’ and habere ‘to have’. English derivatives include “debt”, “debit”, and “due” (the latter via French).

de + habere = debere

sumere ‘to take, assume, obtain’ (derivatives include “consume”, “presume”, “resume”) comes from a fusion of the preposition sub ‘under’ with a verb emere ‘to buy, take’.

sub + emere = sumere

Fusion Words in French and Spanish

Over the centuries during which the Romance languages developed from Latin, the process of word fusion continued: linguistic change is never done!

An instance of fusion common to several Romance languages is that of the Latin preposition ad ‘to, toward’ with the masculine definite article descended from ille ‘that one’, accusative illum: Italian and Spanish al, and its French cognate au (word-final [l] tended to weaken to a [w] sound in French, and the diphthong [aw] subsequently simplified to [o]). For example, ‘in the beginning’ in French is au début.

ad + illum = al / au

A parallel instance involves the Latin preposition de ‘from’: French de + le becomes du [dy]. This fusion is seen in many names, such as Dubois (meaning ‘from the wood’, le bois [bwa]) and Dupré (‘from the meadow’, le pré).

de illo = *del → du

There is an important caveat regarding these fusions in French. The word le is not just the definite article ‘the’, but also a masculine object pronoun ‘him, it’. When it is the pronoun that follows de or à, this combination does not result in fusion! So to say ‘I am interested in doing it’, we must say:

Je suis intéressé à le faire (not *au faire)

The word le is a pronoun here, corresponding to English “it” (not the article “the”). Likewise, to say ‘I forgot to do it’, we would say:

J’ai oublié de le faire (not *du faire)

Modern Spanish has very interesting fusions involving the singular personal pronouns mi ‘me’ and ti ‘you’. When these pronouns are the object of the preposition con ‘with’, the words are written together and a special suffix is added:

‘with me’ conmigo

‘with you’ contigo

These forms descend from Latin fusions of pronouns (me, te) + the postposition -cum ‘with’ (which also occurred as a preposition). Now the Latin word cum is also the source of Spanish con, so these words are redundant: the literal meanings are ‘with with-me’ and ‘with with-you’! Note that the initial sound [k] of cum became voiced to [g] in Spanish when it stood between vowels.

me ‘me’ + cum ‘with’ = migo

te ‘you’ + cum ‘with’ = tigo

Fusion Words in Chinese

Mandarin has a few cases of fusion involving the negative marker bù 不. When this occurs with the future auxiliary yào 要, the meaning may be ‘will not’, ‘cannot’, ‘don’t want to’ or ‘should not’. When the meaning is prohibitive (‘don’t!’), these words may fuse to bié (written 別, which also has other meanings). If we use this prohibitive bié, the main verb cannot be omitted.

bù 不 + yào 要 = bié 別

Another such fusion results from búyòng 不用 ‘need not’ in fast speech: the result is pronounced béng, and it is written 甭 (which combines the graphs 不 and 用 into a single character).

bù 不 + yòng 用 = béng 甭

Classical Chinese was very rich in fusion words; several examples are given in the table below.

Conclusion

As you can see, in many cases fusion occurs when there is a sequence of vowels in unstressed words, as in English “doff” from “do” + “off”, or Latin neuter ‘neither’ from ne + uter. In many cases the second component had an initial consonant that was weakly articulated, such as the /h/ in Latin ne + hemo which gave nemo ‘no one’ or the voiced labio-uvular stop /*ɢʷ/ in Old Chinese *pə + *ɢʷij which gave *pəj 非 ‘is not’.

But by no means is that always the case. The German preposition + article fusions we saw all involved elision of the voiced stop /d/, and several Old Chinese fusions came about by loss of a final vowel, such as the negative *put from *pə + *tə.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief survey. Understanding the composition, meaning, and correct use of fusion words is an important step in mastering a foreign language, and will deepen your appreciation for what makes a language or speech variety distinctive. Keep your eyes and ears peeled for these and other cases of word fusion that might be happening at this very moment!

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!