Ambigrams and Other Cross-Language Wordplay for Language Learning

Hello, LanGorinos! Today we’re going to take a look at some ambigrams, which is a kind of visual word-play with a twist. All of the ones we’ll discuss in this post were created by members of the LanGo team (except the one above and in Figure 2, which is based on one that Tyler saw in Games magazine about two decades ago).

What is an ambigram, you ask? An ambigram is a graphic representation of a word that either reads the same when flipped upside down (see Figure 1), or represents a second word when viewed from a different orientation, as Figure 2 does.

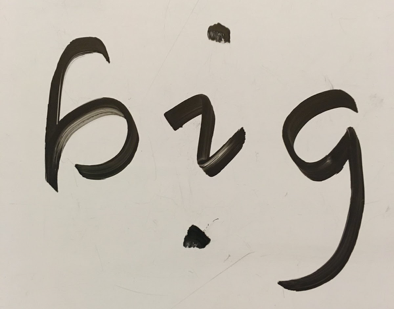

FIGURE 1: Ambigram of the English word “big”.

When this image is rotated 180 degrees, it will again read “big”!

FIGURE 2: happy / holiday.

In Figure 2, viewed one way, the written marks spell the word “happy”. But if we rotate this image 180 degrees... the same image now spells the word “holiday”! In some examples below, we’ll see that the two readings (or ‘messages’) conveyed by an ambigram need not be in a single language.

We LanGoers love ambigrams not only because we appreciate fun and imaginative wordplay, but they can also be great visual mnemonics for vocabulary in your target language. In this post, we present a team-compiled list of several of our favorite English ambigrams as well as some excellent cross-linguistic ambigrams to help learners of other languages (e.g., Korean, Chinese, French, German, Hindu, and Urdu) learn new words in a creative way. We also present several other kinds of cross-language wordplay for the same aim, including dual-writing-system “crossings” and “interdigigrams”. In the ones we’re calling “crossings”, we’ll see cases where two distinct writing systems overlap (see Figures 6, 7, and 12), while “interdigigram” is our term for writing in which two systems interdigitate, or alternate like the fingers of one’s hands when brought together (Figures 9 to 11).

But most importantly, ambigrams and wordplay are a way of having fun! Playing with words (whether made of sound or written marks) allows us to flex our linguistic muscles with more enjoyment than we tend to get from drills or rote memorization. Practicing and memorizing are important, even indispensable skills to us as language-learners; but wordplay lets us take a step back, loosen up and have some fun while we apply the knowledge we have acquired. If having fun with language is something you hate, please do not read this post!

English Ambigrams

Here are two more English ambigrams we really enjoy: “Blessing” in Figure 3 and “awesome” in Figure 4. When these images are flipped upside-down, they will read the same way. Now that’s awesome (x 2)!

FIGURE 3: Ambigram of the English word “blessing”.

FIGURE 4: Ambigram of the English word “awesome”.

Korean Ambigrams and Korean-English Crossings

In this section, we talk about Korean ambigrams and dual-writing-system crossings of Korean and English words that can be helpful visual mnemonics for learning new Korean vocabulary.

The ambigram in Figure 5 involves a single writing system and a single language, and in this one each part of what’s written is essential to the message in either orientation.

FIGURE 5: Ambigram of Korean 해우 hae-u ‘manatee’.

Note that you have to play with the spacing to achieve the desired effect of rotational symmetry, allowing the H-shaped vowel letter <ae> to form a syllable block with the ambiguous <h> ᄒ/우 <u> letter shape on either side.

The crossings in Figures 6 and 7, on the other hand, involve two writing systems and languages, and take advantage of shared letter shapes (the parts in orange) to create visual blends.

FIGURE 6: Dual-writing-system Crossing of Korean 창문 changmun and its English equivalent, ‘window’.

The orange bit of Figure 6, shaped like a circle, is read in Korean as syllable-final ᄋ <-ng> (that is, the velar nasal [ŋ]), and as lowercase <o> in English.

The orange part of Figure 7 below is the letter shape for the aspirated consonant ᄐ <t> ([tʰ]) in Korean as well as a capital <E> in English.

FIGURE 7: Dual-writing-system Crossing of Korean 탁자 takja and its English equivalent, ‘table’.

Chinese Ambigrams and Chinese-English Interdigigrams

Here we show our favorite examples of Chinese ambigrams (see Figure 8), as well as some Chinese-English interdigigrams. The latter term is, we must confess, one that was made up by a member of the LanGo team (if anyone knows a more orthodox name for these things, please get in touch!). The name is a portmanteau (smooshing-together) of the “interdigitate”, which means ‘to be locked together like one’s fingers when the hands are folded’. If you look, you can find look-alike or sound-alike words in different languages from which you can construct short mnemonic phrases.

For example, Spanish has a word sin which means ‘without’; and English has a word “sin”, which is a noun. (If we’re being nit-picky, we may note that though these words are spelled the same, the vowels are not a perfect match: the English word has a lax vowel [ɪ] which Spanish lacks.) The Spanish word meaning ‘sin’ is pecado. Now we can construct a short phrase: without sin pecado. The first word is clearly English and the last clearly Spanish; the word in the middle is both, and the Spanish phrase translates the preceding English one. Chinese examples like this begin with Figure 9.

FIGURE 8: A natural ambigram, Chinese 互 ‘mutual, reciprocal’.

Though most Chinese characters are not symmetrical, a few of them are, including this one. When we write this character by hand the bottom line should be longer than the one on top, so we may have to jiggle the proportions a bit to make the rotation work, similar to what we saw in Figure 5 above.

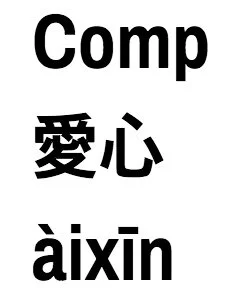

Figure 9 shows a short Chinese-English interdigigram for the words “compassion” and 愛心. The Mandarin pronunciation of ‘compassion’ 愛心 àixīn is, in IPA symbols, [ ɑɛɕin ], which is not far from the sounds [ -æʃn̩ ] heard in the last two syllables of the English “compassion”.

FIGURE 9: Compassion interdigigram.

If you keep an eye and an ear out for happy coincidences like this, you can be spared some of the hard work of rote memorization.

Figure 10 is a play on the U.S. road signs that abbreviate “Pedestrian Crossing” as PED XING, where the crossing lines of the symbol <X> are used as a symbolic representation of the verb ‘cross’. (This is quite like the Chinese character 交 jiāo for this meaning, which comes from a depiction of a human figure crossing his legs: note the X-like shape on the bottom.)

FIGURE 10: Ped 行 xíng 人 rén -- Pedestrian [and Languages] Crossing.

By a happy (non-traffic) accident, the Chinese word for ‘pedestrian’ is 行人 xíngrén--a ‘walking person’--which also has the letter string X-I-N-G. In Pinyin romanization, the letter <x> stands for the voiceless fricative [ɕ] (encountered also in 心 xīn in the last example.) So the string of symbols Ped 行 xíng 人 rén serves as a handy reminder of the meaning of this word 行人 xíngrén, and reminds us of the ubiquity and usefulness of graphic wordplay in our everyday environment.

Pushing this one a bit further, the Mandarin syllable rén (as in 人 ‘person/human being’) calls to mind English “run”--something pedestrians do on occasion. The <e> of the Chinese word is pronounced as schwa [ə], close to the [ʌ] of “run”, and not at all like the [ɛ] of English words such as “when”, “men”. Note that the striding stick-figure on the sign in Figure 10 echoes the shape of the character 人.

In Figure 11, the word for ‘we’ in modern Chinese is 我們, which in Pinyin romanization is spelled wǒmen.

Note that this same string of letters writes the English word “women”, plural of “woman” (both 女人 nǚrén in Chinese, which tends not to express singular/plural distinctions). The sounds of these words differ quite a bit: the Chinese word is, in IPA symbols, [ wɔ mə̃n ], while the English word is pronounced [ wɪmɪn ].

For more cool Chinese-English cross-linguistic ambigrams of which we heartily approve, check out WM Jas Ambigrams.

Chinese-Korean Ambigrams

In Figure 12, we present a neat ambigram that mixes Chinese characters (known in Korean as 한자 Hanja) and the alphabetic Korean script, called 한글 Hangeul. (For more details on Korean writing, see here.) Over centuries of intensive contact, the Korean language took over many loanwords from the neighboring Chinese. In both Korean and Chinese writing, each block-shaped graphic element corresponds to a syllable in the spoken language.

FIGURE 12: Dual-language crossing of Chinese 問 and Korean 문 ‘to ask’.

The Chinese word 問 (‘ask’, read in modern Mandarin as wèn, from Middle Chinese /mjun去/) means ‘to ask’, and the character has two components: the Gate 門 (mén) on top in black ink, and the Mouth 口 (kǒu) below in blue ink. As it happens, the Mouth shape is identical to the Korean consonant letter <m>. When this Chinese word was first borrowed by Korean speakers, it was heard with an initial /m/ sound, and borrowed in the form mun. This syllable occurs in terms such as 의문 uimun and 질문 jilmun, which both mean ‘question’.

As mentioned above, the Korean script is alphabetic: written symbols correspond to specific vowel and consonant sounds. Vowel letters never appear without some kind of consonant letter--there’s even a symbol for a ‘zero’ initial consonant. To write the open syllable /mu/, the <m> shape ᄆ will be on top and the vowel sign for <u> below: 무. The top-to-bottom ordering is maintained when writing the syllable /mun/, where the consonant sign ᄂ <n> appears on the very bottom: 문. (Some vowel signs, such as the <a> seen in 한 han and 자 ja, are written to the right of the initial consonant letter rather than below.)

Because of the shared shape of the Chinese ‘Mouth’ sign 口 and the Korean letter <m> ᄆ, we can unite the two ways of writing this syllable around this shared shape.

French Ambigrams

Two of our favorite French ambigrams are presented in Figures 13 and 14.

FIGURE 13: Dual-reading ambigram of the French words bon ‘good’ and jour ‘day’.

As in the Korean ‘manatee’ example (Figure 7 above), the writer has played with the spacing of graphic components: the stem of the lower-case <b> in bon (above) has to be close enough to the round part to read as a single letter, while upside down (see below) those same strokes must be recognizable as two letters, the <u> and <r> of jour.

FIGURE 13: Single-reading ambigram of French fille ‘girl’.

The French word fille is pronounced [fij] (with the glide [j] as in “yes”, “Hallelujah”), and means both ‘girl’ and ‘daughter’--the latter was the original meaning. To make this word 180-degree symmetrical, your capital <F> will have to be read as an <E>, and <i> will have to double as one of the <l>’s. Figure 13 shows one way to achieve this.

The form fille reflects Latin filia, the feminine form corresponding to the masculine noun filius ‘son’. This pair of words is also the source of Spanish hijo ‘son’ and hija ‘daughter’, as well as the component Fitz- meaning ‘son (of)’ in names like FitzGerald (‘son of Gerald’) and FitzPatrick (‘son of Patrick’). The English word “filly” (meaning ‘young female horse’) is unrelated.

FIGURE 15: Ambigram of German neu ‘new’.

In this German ambigram, lowercase <n> and <u> are a natural pair--keep an eye out for this kind of correspondence when coming up with your own ambigrams. To make a capital <E> 180-degree symmetrical, simply remove the downward stroke (Ξ).

The word neu is pronounced [nɔj], and it is of course cognate with our word “new”--this means that these words come from the same source. Other related words are French nouveau/nouvelle (from which we take the word “novel”), Spanish nuev@, Latin novus/nova, Greek neos/nea (think of “neonate” and “Neapolitan”), Welsh newydd, which all mean ‘new’ (some also ‘young’) and which all reflect Proto-Indo-European *newos, a derivative of *nū ‘now’.

Ambigrams in Other Languages

In this final section, we share examples of ambigrams in other languages.

Hindi/Urdu Ambigrams

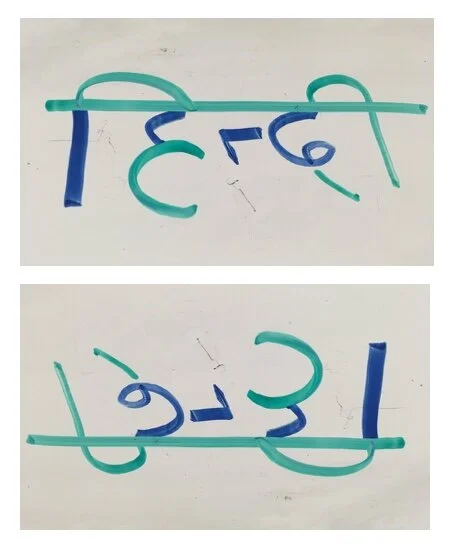

The ambigram in Figure 16 plays on the historical unity of these two modern standard written languages: about a century ago the term “Hindustani” was a common cover term for both varieties. The fundamental grammar is common to both Hindi and Urdu, but the languages differ in where they turn for scientific and other scholarly terms: Hindi draws most heavily from Sanskrit, the classical language of ancient India, whereas Urdu relies on loanwords from Arabic and Persian. Another important difference is in the script: Urdu is written using the right-to-left Arabic script, while Hindi is written in a left-to-right system called Devanagari.

FIGURE 16: Dual-reading dual-writing-system ambigram of the Hindi word Hindī ‘Hindi’ (both colors together, above) and the Urdu word Urdū ‘Urdu’ (in blue below).

To write the word Hindi in Devanagari script, we need to know the basic letter shapes for these three consonants:

the glottal fricative <h>

the dental nasal <n>

the dental stop <d>

There is no separate letter to represent the short and long vowels <i> and <ī>, but two diacritics (the ‘flagpole’ symbols) combine with the consonant letters to indicate the vowel quality of the syllable: the syllable <hi> has the pole to the left of the consonant letter and the flag spanning the two descending stems, while the syllable <dī> has the flagpole to the consonant’s right . The lack of space between the <n> letter and the <d> letter shows that these consonants are in contact, meaning no vowel sound intervenes. When we put these two syllables together, the whole word appears as . This type of system, in which vowels are represented in a way distinct from the way consonants are, is called an Abugida.

Arabic script is closely related to the Phoenician alphabet, which was also the source of the Hebrew, Greek, and Roman alphabets (among many others). At an early stage, writing was done in alternating directions: one line left-to-right, and the following right-to-left, and so on. In this way there was no line break. In the course of their development, early varieties came to favor one direction over the other: Hebrew and Arabic became exclusively right-to-left, while the Greek and Roman scripts went the other way.

The Phoenician alphabet and its early descendants consisted entirely of symbols for consonant sounds; vowels were left unmarked. The language name Urdu (from a Persian word for ‘army’ or ‘camp’) is written with four consonant letters:

the letter Alif for the glottal stop <ʔ>

the rhotic <r>

the dental stop <d>

the glide <w>, which here stands for the long vowel /ū/

The initial vowel /u/ of Urdu is usually not indicated; initial Alif shows that the word starts with a vowel, rather than with the /r/ sound. When the letters are joined together to form a word, they look like this: . All four of the consonant letters in this word are “enders”--they never connect with the following letter of a word, so when writing we must pick up the pen whenever we come to one of these.

Conclusion

We hope you’ve enjoyed our cross-linguistic ambigram sampler from various languages! If any of the languages or writing systems we encountered in this post is new to you, we hope maybe you’ll be motivated to learn more about it. Remember that ambigrams need not involve more than one language--one is plenty. Keep your eyes peeled, and if you come across or up with any ambigrams you like, you can reach us via:

![FIGURE 10: Ped 行 xíng 人 rén -- Pedestrian [and Languages] Crossing.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bb3b241e8ba44ae9c39e05b/1574713208446-485R1EDAWM0ZMFASBQJT/fig10.png)

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!