CJK Correspondences, Part 1

In Part 1 of our Chinese-Japanese-Korean (CJK) Correspondences series, let us compare 漢字, pronounced as Hànzì, Kanji, and Hanja in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, respectively. These characters are used to write Chinese, and many words in Japanese as well, alongside Japanese’s other symbols which represent syllables and are called kana.

The characters are nowadays rarely used in Korea, where people instead use Hangeul, which is an alphabetic writing system devised specifically for Korean. Below we’ll see many examples of Hangeul, which is a super cool writing system; for more details, read Lisa’s post about it.

In this post, we will examine terms for some of the following things in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean:

numbers

places

language names

assorted other examples

And then we will end with a chart of systematic sound correspondences across the three languages.

For an example of what we call “sound correspondences”, you may be familiar with some languages of Europe. Consider this example of similar-sounding words: Spanish dos, English “two”, French deux, German zwei. These words all have the meaning ‘two’ and are similar in form because the languages are related, i.e., they come from a common ancestor language. Look at the correspondences here: Spanish d, English t, French d, German [ts] (spelled z). Square brackets [ ] indicate phonetic transcription using the symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet, or IPA.

In the Far East, many words were borrowed from Middle Chinese into neighboring languages, and sound changes over the centuries have brought about some changes in pronunciation. Middle Chinese was a dialect of Chinese that was spoken around 600 CE. This language, and the associated characters, were introduced to Korea and Japan through the spread of Buddhism. Unlike Japanese and Korean however, Modern Mandarin is a direct descendant of Middle Chinese.

I have been learning Mandarin, Korean, and Japanese and the knowledge discussed in this article will be useful to people in the same situation, because it allows us learners to connect things in our minds and see the correspondences.

Numbers

Numerals are an important vocab set when learning any language, and they also are good examples for the sound correspondences that exist between the three languages. The basic numeral words are shown in Table 1. An asterisk before a word indicates a reconstructed form of a language which is no longer spoken.

Table 1. Numerals in Chinese, Japanese and Korean.

For the numerals ‘1’, ‘7’, and ‘8’, let’s examine their final sounds: <l> in Korean, to <chi> in Japanese, to a lot of <∅> (that is zero, or no final consonant) in Mandarin. These all reflect a Middle Chinese final /t/ sound, and all three languages do something different with this sound.

Let’s look at one case of this, the numeral ‘one’. Japanese added a vowel after the Middle Chinese final /t/ sound. The Middle Chinese word *[ʔiɪt̚ ], ‘one’, was heard as /it/, which is not permitted in Japanese syllable structure. As a consequence, a final vowel /i/ was added: /iti/ (realized now as [i.tɕi], where /t/ is replaced by a palatal sound, like English <ch>). This final vowel sound devoices (meaning it becomes difficult to hear), yielding the pronunciation [i.tɕi̥].

Korean made final /t/ into /l/. This is lenition, or sound weakening, kind of like we do with medial /t/ sounds in English (e.g., in the word “butter”, North American speakers weaken <tt> to a voiced tap, phonetic symbol [ɾ]).

Mandarin got rid of final stop consonants altogether. I bet it’s preserved in Cantonese though; they still allow final stops. Yup, it’s jat¹.

Check out the numeral 五 (5), in Japanese, preserving Middle Chinese initial /ŋ/ like a star. This is the sound at the end of the English word “sing”. English speakers often have difficulty producing this sound at the beginning of words, but in Middle Chinese, it was no problem. Japanese is unique among these three languages in preserving this sound. Rock it, Japanese.

If you look at the number ‘6’, you will see something which is actually quite common. In the variety of Korean spoken in South Korea, word-initial /l/ or /r/ sounds are often deleted, so Middle Chinese */l/ is represented by Korean ∅ (zero) in this word: 육 /yuk/, for older /ryuk/. Similarly, Japanese substitutes /r/ for /l/, so that’s why the form for ‘6’ is /roku/. Also note Japanese words can’t end with a voiceless consonant. (That’s why they added a vowel to the end here, as we also saw in the word for ‘one’, いち ichi.)

Or look at ‘9’. The Middle Chinese form was *[kɨu], which had a /k/ initial, but in modern Mandarin, a lot of these /k/ sounds palatalized (shifted toward the palate, i.e. the ‘roof of your mouth’). Note the competing romanizations of the same Chinese source word: “Peking” (preserved in the name of the university, as well as the way of preparing duck) was replaced by “Beijing” upon adoption of Pinyin romanization by the People’s Republic of China. The <p> to <b> discrepancy doesn’t reflect a change, just a different romanization standard. On the other hand, Japanese and Korean both preserve the velar nature of the initial consonant: J /kyū/, K /gu/. Velar means “produced using the back of the tongue,'' as in the sounds [k] and [g].

Places and Languages

Place and language names are also an important vocab set when learning languages. Here are some great examples of correspondences that exist among the forms in these three languages.

The name of the Japanese capital, 東京 Tōkyō, is from a Chinese compound meaning ‘eastern capital’ (Mandarin Dōngjīng). The Korean form of this name is 도쿄 (Do-kyo), which is similar to the Japanese reading (rather than reflecting the Sino-Korean tradition, where it would be 동경 *Dong-gyeong).

The name of the capital of China, 北京 Běijīng, is a compound meaning ‘northern capital’. Here, too, both Japanese and Korean resort to approximations of modern Mandarin readings: Japanese has ペキン (Pekin, rather than *Hok-kyō), and Korean has 베이징 (Be-i-jing, rather than 북경 *Buk-gyeong).

As you can see in Table 2, each of the names of these three countries uses the same combinations of characters, but in each language the words are pronounced differently, exhibiting similar correspondences to the ones we saw above in the numbers section.

Table 2: The names of China, Japan, and Korea in the languages of those countries.

The names for the different languages are a little more complicated. Let us first look at the name for the Chinese language. In Mandarin, one common term is 漢語 Hànyǔ, ‘the language of the Han people’. In Japanese and Korean, however, one uses 中國語, pronounced Chūgokugo in Japanese and Chunggugeo in Korean. This is the word for ‘China’ as shown above, plus the word for ‘language’.

A similar thing happens in the name for Japan. Even though the Chinese name for the country is 日本 Rìběn, the Chinese delete the second character before adding the suffix which means language, yielding 日語 Rìyǔ. The country name is truncated, and the first syllable stands for the whole. Again Japanese and Korean treat this form differently, but share an underlying structure, both writing 日本語, and pronouncing it Nihongo and Ilboneo, respectively.

One thing I want to highlight here is the difference for the name of the Korean language. In Mandarin, one says 韓語 Hányǔ. Recall their word for their own language, 漢語 Hànyǔ. The only difference in the pronunciation of these words is the tone of the first syllable (shown by the accent mark above the letter A). Another form in Chinese is 朝鮮語. The Japanese name of the Korean language is 韓國語 Kankokugo, and the Korean name is 韓國語 Hangugeo.

Based on this, we see that it is not just one-to-one sound correspondences that describe the differences between languages, but many words have different structures as well, as we have just seen. However, now you have a grasp on some of those differences.

Assorted

Here are some other assorted examples of correspondences across these languages. Shown in Table 3 are a few examples where the meanings remain constant across the three languages.

Table 3: A few assorted words that have the same meaning in all three languages.

Here are a few examples where the cognates occur with different meanings in different languages: C xiānsheng, J sensei, and K seonsaeng, 先生. In Japanese and Korean, the compound means ‘teacher’, but in Chinese, it means ‘mister’, while the word for ‘teacher’ is 老師 lǎoshī.

Or take a look at this one: C xiězhēn, J shashin, and K sajin. The Japanese and Korean terms mean ‘photograph’, while Chinese 寫真 xiězhēn means ‘portrait’ .

For quick reference, Table 4 below summarizes systematic initial sound correspondences across the three languages discussed in this post.

Table 4: A summary of the sound correspondences discussed in this blog post.

Now you have seen some similarities that I have noticed in my study of these languages. Hopefully this should help you in your learning of these languages, or you just found it entertaining, or both! If you wish to review the numerals in the different languages, please check out this cool LanGo Tinycards deck that Tyler made, and check out our other decks there for vocab in Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and all the other languages we teach at LanGo!

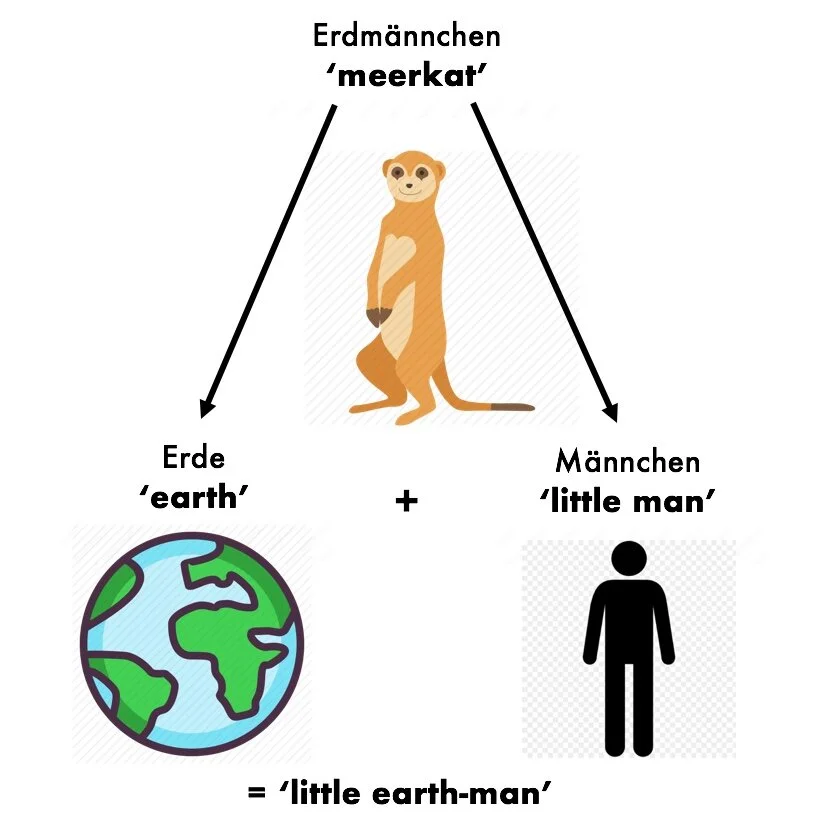

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!