French🐱Chat, Part 2

One common complaint I hear from potential students of French is that the spelling system is so complicated and irregular. My aim in this post is to show that, while there is indeed a lot going on with French spelling, it is actually quite regular—particularly when compared to the spelling of English: consider the various ways the 4-letter string -ough is pronounced in the words tough, though, trough, thought, through. In no two of these words are these letters pronounced the same!

Something that seems to give people trouble with French spelling is the frequent occurrence of silent letters—that is, written letters that do not correspond to any of the sounds that are pronounced. As speakers of English, this shouldn’t trouble us too much. If we’re honest: spelling can often be subtle, and there’s no need to impugn or malign French for silent letters that change the value of another letter!

(Take a look—or rather a listen—to the letters in that last sentence that I underlined: what is their phonetic value?)

THESIS:

French spelling is highly regular,

and occupies a happy middle ground between historical transparency and phonetic accuracy.

A couple points to keep in mind:

To the linguist, it is the spoken language that is primary, and the written language is just a visual means of representing and recording thoughts using words from the spoken language. Consider your own acquisition of your native language: Did you learn to read and write it first, before speaking it, or was it speech that you mastered first?

Over time, languages change: words fall into disuse, new words and expressions arise and gain frequency, and pronunciation changes over time. The pronunciation of words always varies from place to place, from speaker to speaker, and even for a single speaker from situation to situation. What causes these changes in pronunciation is not entirely known, and there may be many causes, but the fact that it does change is universal.

Letters represent sounds, but letters and sounds are not the same thing! One is an acoustic phenomenon perceived with the ears, and the other is a graphic pattern perceived with the eyes. Just because a letter is part of the standard spelling of a word does not mean that the sound most often associated with must be pronounced. There is t in the English words “soften”, “fasten”, “hasten”, but when the word is pronounced, we don’t hear the sound [t]. Listen carefully for it, and also check if your tongue-tip touches behind your teeth in the middle of those words, as it does to make the sound [t]!

French belongs to the Romance language family, alongside Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and a few others. This means that it is the modern descendant of the form of Latin speech that was spread across Europe two millennia ago by Roman soldiers. Because we are lucky to have very detailed information about Latin (in the form of written records), we know quite a bit about many of the sound changes that have occurred in these languages over that time. While Italian is a language that has been very stable and resistant to change (many words and phrases of Latin are easily intelligible to Italian speakers today), French has diverged a bit more from its linguistic ancestor, likely due to contact between people speaking different languages (especially Celtic and Germanic).

To discuss speech sounds, I will make use of the symbols (always in square brackets) of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). The basic principle of IPA transcription is: one sound represents one letter, and one letter represents one sound. This makes IPA transcription quite different from traditional spelling systems like those of French and English. As speakers of English, we have inherited, with a few modifications and additions over the centuries, the alphabet of the Romans, whose language (Latin) had a somewhat smaller inventory of sounds than ours, and who therefore needed fewer letters. What often happens when the alphabet is adapted to write other, newer languages is that people represent single sounds using combinations of letters. Let’s start by examining such cases in French.

Digraphs: Single sounds represented by two letters

Combinations of two letters representing single sounds have quite stable values in French. We’ll start with a few vowel sounds, and then examine some combinations involving consonants.

Vowels

ai

Unless this is written with a diaeresis over the i (ï, as in haïr ‘to hate’), ai represents a single sound [ɛ], which is the English “short E” sound as in “net”. Note that this vowel sound is intermediate between the vowels /a/ and /i/, /a/ being the lowest vowel (meaning the mouth is open wide), and /i/ one of the highest (mouth closed). Examples of French words with this ai: lait [lɛ] ‘milk’, fait [fɛ] ‘fact; done, made’, sait [sɛ] ‘knows’ (the present form of savoir).

au

This too represents a vowel that is intermediate between the values of the letters that make up the digraph: in this case the vowel is [o] (roughly as in English “go”, but a pure vowel), which lies between low /a/ and high /u/. Examples: aucun [okɛ̃] ‘not any’ and animaux [animo] ‘animals’ (plural of animal).

ou

In this case the sound of the digraph is not intermediate between /o/ and /u/, but instead simply the pure [u] (roughly as in English “do”, but a pure vowel). When the value of French simple u shifted to front rounded [y], French speakers had to find another way to represent the back rounded vowel [u]. Compare the situation in Greek: after the value of Υ/υ Upsilon had shifted forward to [y], speakers used the letter combination ΟΥ/ου to represent [u]. French examples: oublier [ublije] ‘to forget’, doute [dut] ‘doubt’ and fou [fu] ‘crazy’.

Consonants

ch [ʃ], [k]

In English the most frequent value of ch is the sound [ʧ] as in “church”, but note that it is not pronounced that way in “chemistry” [ˈkɛmɪstri] or “chic” [ʃik]. In Old French the value was also [ʧ], but over the centuries this sound shifted to [ʃ] (the sound of English sh -- the same sound change is, I’m told, also occurring in regional dialects of Spanish, where muchacho is now pronounced [muʃaʃo]). French examples of ch = [ʃ] include 🐱 chat [ʃa] ‘cat’, chien [ʃjɛ̃] ‘dog’, choux [ʃu] ‘cabbage’, acheter [aʃte] ‘to buy’, and sachant [saʃɑ̃] ‘knowing’.

In a few French words of Greek origin, ch is pronounced [k] (parallel to how th is pronounced [t], see below). Examples: chaotique [kaɔtik] ‘chaotic’, chlor [klɔʁ] ‘chlorine’. Note that the English equivalents are also pronounced with [k] instead of [ʧ].

gn

Many Romance languages gained a third nasal phoneme in addition to Latin’s /m/ and /n/, namely the palatal nasal [ɲ] (roughly, the consonant in the middle of “canyon”). Because this was a new sound in these speech communities, there was no single letter to represent it, so various spellings were invented in different places to satisfy this need. In Portuguese one writes nh for this sound (English got “piranha” from Portuguese, though we don’t normally pronounce it the Portuguese way); in Spanish people at first wrote nn, but ultimately the abbreviated variant of this, ñ, won out. In Italian and French the spelling gn was adopted. French examples: oignon [waɲɔ̃] ‘onion’, gagner [gaɲe] ‘to gain, win’, agneau [aɲo] ‘lamb’.

ph

As in English, this letter combination primarily in occurs in words of Greek origin, and it is pronounced [f]. French examples: philosophe [filɔzɔf] ‘philosopher’, phonétique [fɔnetik] ‘phonetic; phonetics’, physique [fizik] ‘physical, physics’.

qu

In Latin the sequence qu represented a single sound, the labiovelar stop [kʷ]; that is, [k] pronounced with rounded lips. In English we approximate this with the sequence of consonants [k] + [w], as in “quick” [kwik]. In Standard French, on the other hand, Latin [kʷ] developed to a simple [k] without exception. Examples: quatre [katχ] ‘four’, quel [kɛl] ‘which, what?’, quitter [kite] ‘to leave, depart’, quotidien [kɔtidjɛ̃] ‘everyday’.

th

This digraph is very common in English, where it is pronounced

as [θ] in words like “think”, “with”;

as [ð] in a smaller set of words such as “the”, “this”, “then”, “weather”, and

as simple [t] in a tiny number of words like “Thomas”, “Neanderthal” (for hyper-correct speakers, as the word is borrowed from German). As French lacks the first two of these sounds, the letters th will only be pronounced as [t], as in loanwords like thé [te] ‘tea’, théâtre [teatχə], mythique [mitik] ‘mythical’.

Single letters: Consonants

Now that we’ve reviewed some two-letter combinations whose phonetic values are very stable, let’s look at some single-letter spelling-sound correspondences. We will examine tricky cases (like the letters c and g, whose values depend on neighboring sounds) in a future post.

b, d

The values of these letters are always voiced stops [b] and [d], respectively, unless they stand at the end of the word (where they tend to be silent, as in nid [ni] ‘nest’).

f

This letter always represents the voiceless fricative [f], as in fin [fɛ̃] ‘end’, plafond [plafɔ̃] ‘ceiling’.

h

Historically distinct are H muet [aʃ mye] ‘mute H’, derived from Latin, and H aspiré [aʃ aspiʀe] ‘aspirated H’ in words of Germanic origin, such as haïr ‘to hate’ and the place-name Le Havre [lə avʀᵊ]. In modern French, both types of h are always silent, but they behave somewhat differently: before a word beginning with mute H, the vowel of the definite article will be dropped. So ‘the man’ is l’homme [lɔm] (and not xle homme), and ‘the hour’ is l’heure [lœʀ] (and not xla heure). But with the aspirated H, this vowel-dropping does not occur, so the place-name is Le Havre [lə avʀᵊ], and not xL’Havre x[lavʀᵊ].

j, v, z

With the exception of word-final z which is most often silent, these three consonant letters have very stable phonetic values. The letter j always represents voiced [ʒ] (except in words borrowed from English like jogging). Examples of French words with j: juge [ʒyʒ] ‘judge’, juste [ʒyst] ‘just, right’, joie [ʒwa] ‘joy’. Letter v always represents voiced [v], as in voie [vwa] ‘way, track’, livre [livʀᵊ] ‘book’, vivre [vivʀᵊ] ‘to live’. Unless it’s silent in word-final position, z represents voiced [z], as in zèle [zɛl] ‘zeal’, onze [ɔ̃z] ‘eleven’, douze [duz] ‘twelve’.

k, p, q

While the letter k in French is restricted to loanwords and recently created words like kilomètre ‘kilometer’ and kiosque ‘kiosk’ (where it is pronounced as [k]), p and q always represent the sounds [p] and [k], respectively. Examples of p include point [pwɛ̃] ‘point’, approcher [apχɔʃe] ‘to approache’and couper [kupe] ‘to cut’.

Note that the letter p is silent in a few cases, when it occurs between two consonants, as in compter [kɔ̃te] ‘to count, plan’, and word-finally as in loup [lu] ‘wolf’ and coup [ku] ‘a hit, a blow’.

l

The letter l always represents the sound [l] in French. Note that the English [l], especially that of North American speakers, is much darker-sounding than the French [l].

m, n

In the onset of a syllable, m and n represent the consonants [m] and [n], respectively, just as in English. Examples include mère [mɛʀ] ‘mother’, aimer [eme] ‘to love’, femme [fam] ‘woman’; and notre [nɔtχᵊ] ‘our’, année [ane] ‘year’, and bonne [bɔn] ‘good (fem.)’.

In the coda of a syllable (that is the part following the vowel, before the onset of a following syllable), these letters (and the digraph ng) represent not a consonant segment, but the feature of nasalization of the preceding vowel -- that is, our internal articulators move in such a way that air escapes through the nose as well as the mouth. This can be heard in French words such as bon [bɔ̃] ‘good (masc.)’, nom [nɔ̃] ‘name; noun’ and many others. Modern French only has three nasal vowel sounds [ɛ̃ ɑ̃ ɔ̃], and there are many homophonous words involving these: cent ‘hundred’, sans ‘without’, sent ‘feels, smells, tastes’, sens ‘sense, meaning’, and sang ‘blood’ are all pronounced [sɑ̃].

r

The French r sound has a uvular articulation: the basic value is [ʀ], and when it occurs next to a voiceless consonant it is devoiced to [χ]. The former value is heard in words such as rire [ʀiʀ] ‘to laugh’, rien [ʀjɛ̃] ‘nothing’, and it occurs for example in lettre [lɛtχᵊ] ‘letter’ and porter [pɔχte] ‘to carry’. The last example shows another important fact about the letter r: at the end of a word after e, it colors the neutral e to the front mid vowel [e] and is itself silent. This is a very common infinitive ending, and it corresponds to the Spanish ending -ar, and to the Latin and Italian -are: aimer [eme] ‘to love’ (compare Sp. amar, Lat. It. amare), porter [pɔχte] ‘to carry’, and oublier [ublije] ‘to forget’, which were all mentioned previously.

SUMMARY

In this post we’ve examined some spelling-to-sound correspondences in Standard French, starting with two-letter combinations of vowels and consonants, then moving on with single-letter consonants. All the consonants discussed here are shown in the table below. Our survey will continue in the next French post.

In the next post, French🐱Chat, Part 2: Single consonant letters with multiple phonetic values and single-letter vowels.

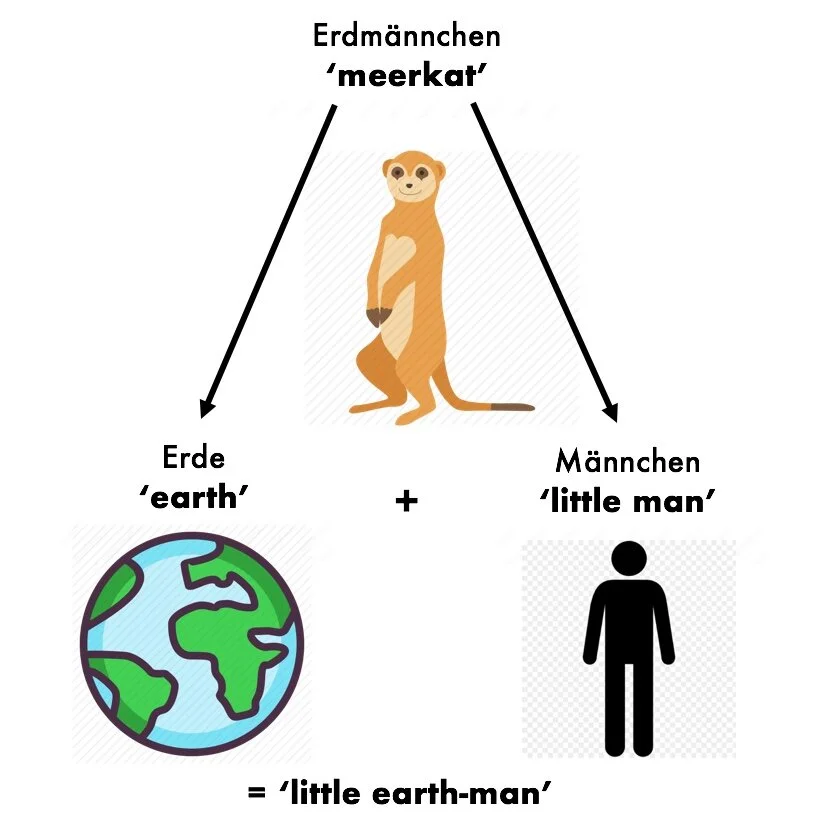

Tools for helping you master some of the trickier points of German grammar, whether you’re learning it for the first time or wanting to review the fundamentals. Los geht’s!